COVID-19 Illuminates the Danger of Ignoring Problems That Exhibit Exponential Growth

Stevens professor Philip Orton explains how small problems can grow into crises, advising that now is the time to listen to lessons from the Earth

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, communities across the world are learning hard lessons: about the fragility of life; the importance of our relationships and support networks; for many, the impermanence of work and stability; and countless other values we are forced to take a close look at during this difficult time.

The Earth too, it seems, has lessons to offer.

With transportation and industry production having come to a near halt in many metropolises, we have seen China’s carbon emissions cut by 100 million metric tons; we have seen the water in the iconic canals of Venice become so clear that one can see swimming fish; we have seen air pollution drop by 30 percent over major cities in the northeastern U.S.

While this cleanup of our environment is likely a temporary byproduct of the pandemic until we return to “business as usual”—according to Philip Orton, research professor of ocean engineering in the Department of Civil, Environmental, and Ocean Engineering (CEOE) at Stevens Institute of Technology—we are faced with yet another lesson: the importance of acting early amid threats that explode with exponential growth.

With a hyper-contagious virus sweeping the world, we are witnessing literally countless numbers of infected individuals, because we haven’t the resources to test everyone. Worldwide, we have lost 176,786 lives as of April 22, that we know of. And how long did it take for that total number of confirmed deaths to double? Just ten days, according to Our World in Data.

As the globe waits in fear and apprehension for the deadly virus to reach its peak, or at least plateau, and longs for a return to normalcy, Orton suggests that now is the time to take a sober look at the dangers of exponential growth and the importance of early action.

“Exponential growth blows people’s minds; it’s hard to understand,” said Orton. “This [situation] is unfortunately making it much more tangible.”

Orton explained that US scientists gave warning to take preventative measures in preparation for the virus to cross its borders in February, yet it was not until March that we took substantial action, allowing more time for the virus to rapidly spread after the first US case was confirmed in Snohomish County, Washington on February 20.

Similarly, scientists warned of global warming between twenty and thirty years ago; yet with little action to reduce carbon emissions since then, today we are experiencing a global average temperature of about two degrees Celsius higher than it was in 1880 during the pre-industrial era. That number may seem small, but it’s significant; and we on land are fortunate that 90 percent of the heat has actually been absorbed by the ocean—albeit at great costs to oceanic and wildlife health—instead of staying in the atmosphere. The result of this is slowly building, but it’s accelerating sea level rise.

Orton researches coastal flooding and climate change at the Davidson Laboratory in the Charles V. Schaefer, Jr. School of Engineering and Science, where he also helps advise the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey on water and flood levels, among other research and teaching activities

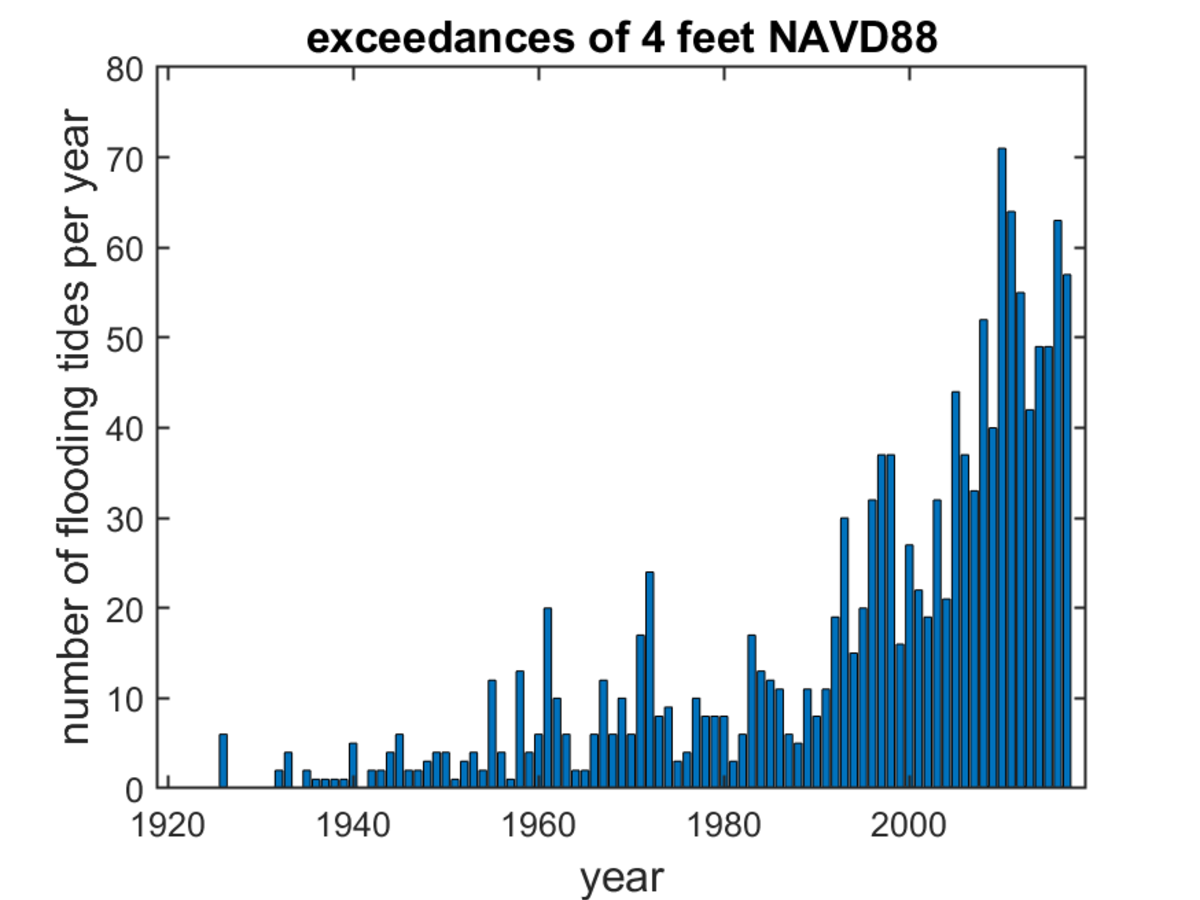

“Due to sea level rise, many locations are seeing an exponential growth of the number of floods per year, and rapidly approaching being uninhabitable” he said. “For example, in some neighborhoods of Miami, Atlantic City, and for New York City—the Hamilton Beach neighborhood near the John F. Kennedy International Airport—we used to see sporadic, occasional floods year-to-year; but now these are happening about 30 to 50 times a year. Before the exponential growth set in, floods were caused by random, extreme events.”

These sites are unusually low-lying neighborhoods built on landfill over wetlands. However, a dramatically larger population lives on coastal property within a few feet above this level, and is threatened in future decades by this same exponential increase in flooding. These future chronic flood zones have property valuing in the trillions of dollars and are still being developed with new homes.

Verified cases of COVID-19 were doubling every few days at their worst, whereas these locations are seeing floods double every decade or so. But there is another critical difference: The response time to slow COVID-19 is weeks-to-months, with people sheltering at home. The response time to slow global warming is decades.

“If we had heeded scientists’ warnings and reduced global greenhouse gas emissions 20 or 30 years ago when we were first warned about it, we wouldn’t be in this situation now.”

Orton says that because the US lock-down began in mid-March instead of late February, it allowed doubling every two-to-three days for three weeks, leading to about a 500-fold increase in the number of infections. This put us beyond the point where sheltering and our limited capacity for testing could have prevented the outbreak.

While the cleanup of water and air quality that we’ve seen in recent months is astonishing, Orton explained that “the huge dent in carbon emissions this year...won’t have much impact on global warming, if it’s short term.”

Paradoxically, Orton commented that we may even see a small uptick in global warming in 2020, because particulate air pollution blocks sunlight, and with the reduction in these particles there will also be an uptick in sunlight. “The effect of particulate matter is greater than scientists once realized,” he said.

“The key issue with the CO2 emissions [we are seeing now],” he continued, “is it’s temporary. We can learn about it, but it’s not going to affect much change. A, say, ten percent decrease for just one year is minor, because CO2 lasts in the atmosphere for decades or longer.”

Orton concedes that we are experiencing a bittersweet lesson that sheds light on a problem without solving it. “We want fewer greenhouse gases per economic unit, but we now have decreased economic units. This is not a good thing.”

Much of the reduction in greenhouse emissions is because people aren’t traveling as much. Just one sport utility vehicle (SUV) can emit several tons of CO2 into the atmosphere annually. With SUVs holding 39 percent of the car market share, that amounts to 700 million tons of annual CO2 emissions. Those emissions are second only to the power sector.

“I’m not anti-car,” said Orton. “...We can keep the reduction we are seeing now by putting in place policies that encourage more work from home, rather than [requiring] office space and commuters. There is an opportunity here to make some more sustained and impactful changes.

“You can’t solve these problems efficiently if you let exponential growth set in,” he continued. “Then we may have waited too long to enable minor adaptations to be effective, whether it be to shelter in place for coronavirus, or to move your car up your driveway to higher ground to avoid flooding.”

Many wonder if the world we return to after the pandemic ends will be forever altered. We are interacting with technology differently; we are calling our loved ones more frequently; we are working creatively; we are volunteering to help wherever possible. Perhaps we may change how we interact with our environment, too.

“It’s an interesting experiment we are living in,” Orton said.