New York Underwater? Stevens' Resiliency Experts Work to Plan and Prepare

As waters rise and storms increase, the university assists NYC, the Port Authority, the Coast Guard and others with expertise and warning tools

Some neighborhoods of New York City flood five times a month. More will begin flooding monthly (or even more often) during full and new moons as soon as the next few decades.

And a few sections of the Big Apple could go permanently underwater in as little as 80 years if global carbon emissions aren't scaled back or protective measures for the city aren't undertaken.

That's the frightening conclusion of the New York City Panel on Climate Change (NPCC), which periodically studies the issue with a cadre of leading regional experts.

Now Stevens — which contributes research and other input to the panel's reports — is helping New York City and other urban and coastal communities prepare for this uncertain future with leading-edge resiliency research.

"Sea level rise is accelerating, including ice cap melting," explains professor Philip Orton, a technical advisor to the NPCC since 2013. "The worst case, we found, is now a nearly ten-foot rise in the average sea level in the metro NYC in just 80 years.

"If that scenario came to pass, daily high tides would match Hurricane Sandy’s flooding."

Why the worst-case is now worse

Less than a decade ago, the worst possible scenario for NYC was calculated as "only" a six-foot rise, which is bad enough. But now the worst case is considered much worse. Why? Global ice sheets are melting much faster than expected.

"We included a new worst-case scenario," notes Orton.

And even if a ten-foot rise doesn't come during this century, without global action to reduce atmospheric warming it will come eventually. Since New York City isn't going anywhere, something's going to have to give.

In fact, that process has already begun. In the New York-New Jersey region, the Atlantic Ocean has risen relative to the region's landforms by about 13 inches during the past century alone.

No big deal? Actually, it is. Even a conservative projection of sea level rise calls for normal, non-storm levels of water that sit two to four feet higher than they do right now... by the year 2100. (It'll come even higher up during storms, of course.)

For low-lying boroughs and a city mostly laid out one to two centuries ago, that would be potentially devastating.

"We're talking flooded streets, homes, high-traffic expressways and boulevards, subways," says Orton. "The infrastructure of the city was not engineered to factor in the sea rising and frequently flooding inland. And now that's going to become a problem."

Inevitable inundation?

The problem of rising seas wasn't predictable when the city’s infrastructure was originally built in the 19th century. We didn't have the methods, observations or data to recognize a process that was already beginning.

But the sudden warming of the Earth's atmosphere over the past century, and particularly over the past couple decades, has been a shock to the system, melting the polar ice caps and sparking heat waves, hurricanes, wildfires and flooding now familiar from the evening news.

That same process is also nudging ocean levels gradually, and dangerously, higher. As humans burn more fossil fuel, gases are produced and rise. But they don't leave the earth's atmosphere entirely. Instead, they linger very high above, like insulation.

The atmosphere begins to warm. That causes oceans to warm. Warmer water fuels stronger hurricanes. And those heavier storms and higher winds bring more flooding during storms, pushing higher, heavier waves and tidal surges farther inland.

For low-lying coastal cities like Miami and New York, partial inundation is now all but inevitable.

"Coastal floods are becoming more common due to climate change," concedes Orton. "That is absolutely known. The indisputable effect of sea-level rise comes into play."

If protective measures are not undertaken, areas of Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island will lose real estate and flood first and most often, he says.

And hundreds of other coastal communities in the nation, once believed safely protected from the ocean's brute force by beaches, berms, seawalls or distance, will soon be under the gun as well.

Responding with a three-pronged attack

To support city, regional and federal officials as they ready new plans, warning systems and defenses to protect the Big Apple, Stevens researchers are simultaneously examining the issue of climate change from at least three different perspectives.

Stevens' historic Davidson Laboratory is a national leader at forecasting — and warning of — sudden, storm-driven floods and tidal surges, which will likely become more frequent and intense in the city as the climate continues to warm.

At the same time, Davidson Lab researchers are working to get a handle on the longer-term effects of climate change on homes, skyscrapers, barriers, beaches, business districts and almost everything else in the urban and suburban communities surrounding New York Harbor.

And Stevens experts design and test both natural and built physical defenses that carefully balance the region's growth, culture, aesthetic and physical constraints with changing climatic, meteorological and ocean conditions.

"All three of these areas are critically important," notes Davidson Lab Director Muhammad Hajj. "It's critical to get the event-forecasting piece right, because this saves lives, reduces adverse economic impacts and provides officials with time to warn the public, evacuate if needed, move critical infrastructure and otherwise prepare for extreme-weather events."

Evolving models that forecast better than ever

How will do' storm-surge models and forecasts lend a hand?

Science, plus a touch of art.

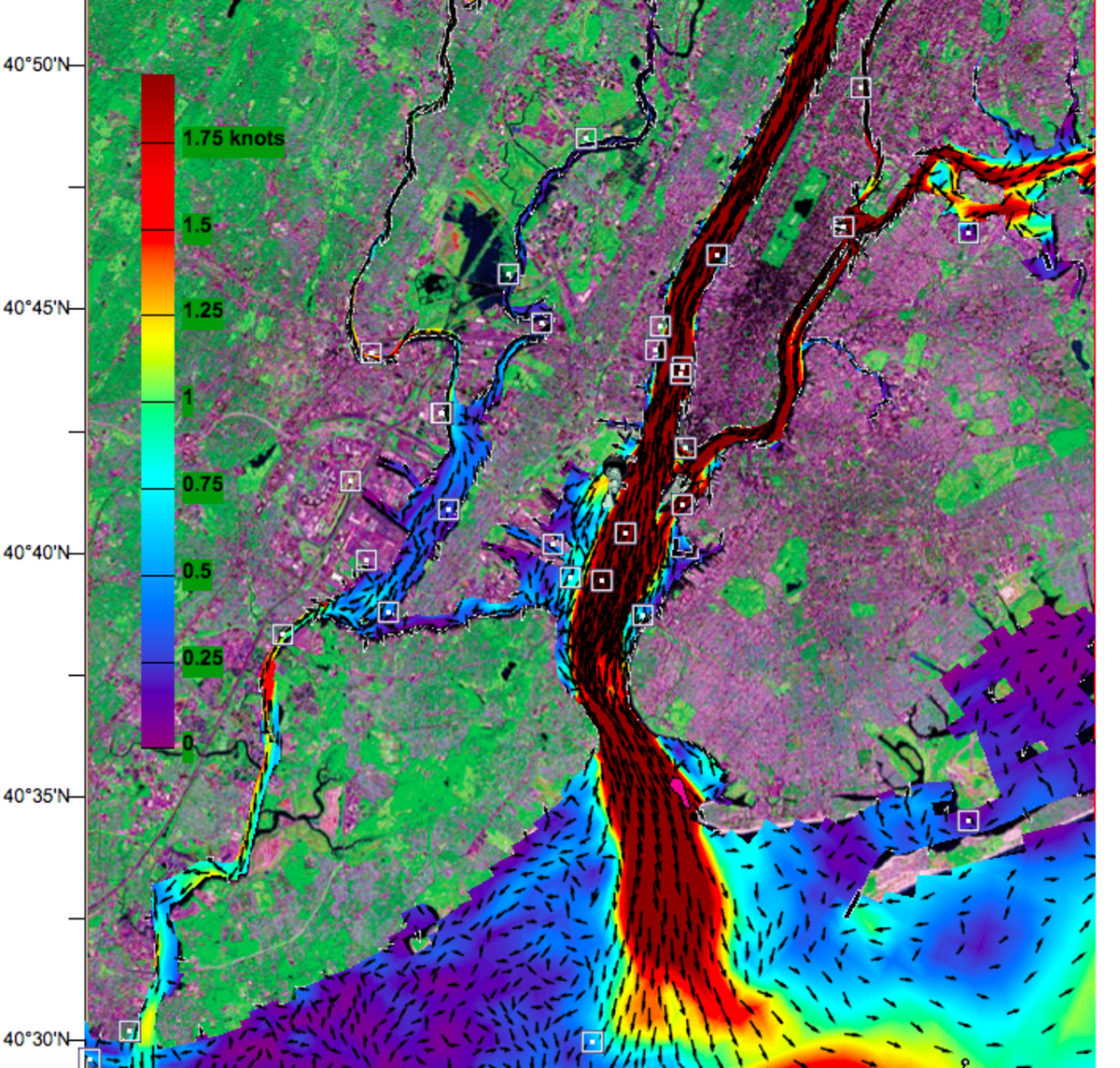

The secret sauce began with the Stevens Estuarine and Coastal Ocean Model (sECOM), a "probabilistic" mathematical model developed at Stevens now considered among the best in the world at modeling urban-ocean environments. sECOM forms the backbone of both NYHOPS and SFAS, the university's two primary forecast and visualization tools.

Davidson Lab researchers including Orton, Raju Datla and Jon Miller continually tweak the models' math to make their simulations and forecasts faster, more powerful and more accurate. The lab has evolved the physics within the model to account for the ways in which waves enhance wind-driven storm surge — a key factor in flood and surge predictions.

And the team has also updated the system by expanding its models to cover a larger region of the Atlantic Ocean so that it can better forecast the effects of very large storms like Irene and Sandy.

All those tweaks are adding up: the university now supplies partners like the U.S. Coast Guard and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) four-day advance forecasts of conditions.

“Davidson Lab provides us tactical information on the risk of coastal flooding that we use for decision-making and hazardous-weather preparations,” says Sal Kojak, a director in PANYNJ’s emergency management unit. “This partnership enhances our situational awareness so we can issue alerts, prepare for coastal flooding and mitigate losses.”

Fighting floods, street by street

Sandy's power, placement and timing combined to produce the highest floods and storm surges ever recorded in the city. The superstorm brought an 11-foot storm tide to New York Harbor, killed more than 200 people and caused approximately $70 billion in property damage to the Eastern Seaboard.

Several years of work were required to rebuild beaches, homes and communities.

Determined not to be caught off guard again, state and federal officials immediately reached out to Stevens for support in Sandy's wake.

"Especially during extreme events, our predictions are sought by different entities for assessment of vulnerabilities, identification of potential impacts and development of preparedness plans throughout New Jersey and New York," notes Hajj.

The Davidson Lab team has created street-by-street flood and storm-surge forecasting maps for New York City planners. Those maps and models help agencies warn residents sooner about specific surge and flood threats and plan evacuations.

Other local officials in the region access the university's daily public updates, as well — then use them when preparing for storms.

"Most days, the Stevens Flood Advisory System is the first piece of information I check in the morning," says Caleb Stratton, Chief Resilience Officer for the city of Hoboken.

"Accurate records and projections of surge allow us to escalate our emergency operations in real time and make informed decisions."

Steven built additional tools, models and warning systems that predict floods in Hoboken and the New Jersey Meadowlands for New Jersey Transit (NJT) to help NJT reposition equipment to safer areas before high surges and warn commuters prior to predicted flood and surge events.

Davidson Lab researchers have also produced visualizations of climate change-driven floods for the city of Philadelphia; dramatic modeling of the long-term effects over time of sea-level rise on Jamaica Bay (where much of the land surrounding JFK Airport would be swallowed up); and the Hudson River flood plain.

Engineering better resilience

Stevens' historic legacy in engineering also comes into play when helping communities prepare for stronger storms:

Stevens faculty advised teams in the national Rebuild by Design post-Hurricane Sandy competition, including a winning proposal to build a series of natural breakwaters off the southeastern shore of vulnerable Staten Island.

Faculty and student researchers developed a prize-winning solar-powered home that can withstand hurricane-force winds (and close its own shutters to resist rising flood waters).

Orton works with flood-prone communities in New York City, including Broad Channel and Hamilton Beach (both in the borough of Queens), to inform residents and discuss preparations and defenses with local planners and officials.

He has also advised Jersey City, New Jersey's second-largest city (population: 270,000), on engineering and landscaping plans to direct flood waters around (rather than into) the city, and he investigates the pros and cons of gated barriers that could be locked shut during strong surges to reduce damage.

Marsooli works to quantify sea-level rise and extreme-weather events in the metro region driven by climate change through modeling and other techniques, working with partners such as Princeton University.

And Miller continues to monitor and study beach erosion and replenishment techniques, including "living shorelines" that work to absorb the force of high waves, strong surges and sea-level rise. The U.S. Army has supported his research.

"We have a responsibility to provide and continually enhance our modeling ability," summarizes Hajj. "Communities and agencies urgently look to Stevens for this critical data in times of need.

"The university will continue to serve communities and the government by helping in the preparation for sudden extreme-weather events, as well as for the more gradual, but also devastating, effects of gradual sea-level rise."