Danielle McPhatter ‘18 has found herself blending art and technology at Nokia Bell Labs.

The headquarters of Nokia Bell Labs sits on a sprawling campus in Murray Hill, New Jersey, where engineers and scientists have made more advancements than can possibly be listed. The company’s extraordinary nine Nobel Prizes speak to the momentous progress they’ve made within science and technology though, and to this day, the institution leads the way in telecommunications, 5G networking, industrial automation and more. It’s also here where one Stevens alumna finds herself working in the most human of fields: the arts.

Once a music and technology student, Danielle McPhatter ‘18 now works as a researcher within Nokia Bell Labs’ Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) Lab. In this role, she collaborates with more than two dozen artists, acting as a translator between them and the company’s engineers. This means that McPhatter’s everyday responsibility is to bolster artistic vision with the world’s most cutting-edge technology.

“It’s really a bidirectional feedback between the artist and the engineer,” notes McPhatter, as she describes how E.A.T. operates. By connecting these professionals, E.A.T. strives to humanize technology and create immersive experiences that far exceed the spoken or written word. The research vision is to develop new ways for people to emotionally connect and to forge deeper understandings across humanity. Therefore, artists are brought on for short-term collaborations or artist-in-residence programs, the latter lasting one year or more to maximize meaningful exchanges across disciplines.

“The artist walks away with so much more scientific, technical knowledge about what their options are and how big their universe can expand in terms of expression,” says McPhatter. In turn, engineers discover new uses for their technology, giving them novel directions to explore. “That’s been a really good ecosystem when it comes to developing a lot of the technology that we actually have in house.”

Consequently, McPhatter often finds herself working with artists in rather avant-garde spaces. To start, there’s the antechamber, a room lined with speaker after speaker, enveloping those who visit in sound. Then there’s its opposite, the anechoic chamber, which was once the quietest room on Earth.

Completed in 1947, the space is lined with fiberglass wedges, and cement and brick make up its outer walls. The room is quiet — very quiet — and McPhatter jokes that visitors can hear their own biology. The swish of a tongue, the pop of a knuckle, sometimes even a heartbeat, they all become audible when the room is prepared for absolute silence. Doing so takes a bit of prep and involves shutting a massive half-cylinder door and turning off all the lights. This leaves visitors feeling as though they are floating in space, floating in silence, floating in darkness. The absence of sensorial stimulation can be unnerving at first, but over time, an artist can use the sensation to focus on a thought or explore their imaginations.

Recent experiments within these spaces have used the Sleeve, a piece of wearable technology the enables users to control the spatial elements, volume and timbre of sound simply by moving their arm. “This is a very exciting step for us in the world of new musical interfaces and embodied instruments,” says McPhatter. “To augment the performer by transforming any instrument into an extension of the body gives us a natural and more intuitive way to control sound and our immersion in it.”

These rooms are playgrounds for creative thinking and performance, and connecting artists with these experiences has become a real passion for McPhatter. “My goal is always to make the thing I develop or create to be as flexible as possible for artists’ expression,” says McPhatter. “At the end of the day, it’s not about the technology, it’s about the piece of work that comes out of the technology.”

Working with Stevens’ assistant professor of music and technology and E.A.T.’s artist-in-residence, Lainie Fefferman, was the first time McPhatter felt truly connected with this work. As a Nokia Bell Labs intern, McPhatter helped build a multichannel live-streaming network, which allowed Fefferman to turn audience members’ phones into speakers during her performance “White Fire,” an electroacoustic reflection on heroines from the Hebrew Bible held in Brooklyn’s Issue Project Room.

“Seeing the output of that for the first time live in this performance that she did was just like, ‘Wow,’” says McPhatter. “Damn, that really works.”

At Stevens, McPhatter built a technical skill set spanning music production, game design and computer science, allowing her to excel within these projects. Yet, this academic and professional direction was unexpected. After studying music composition and theory at Newark Technical Vocational High School, the Irvington, New Jersey, native thought she’d study software instrument design and eventually create songs for children’s shows and video games. But taking a few technology classes in Stevens’ College of Arts and Letters completely changed McPhatter’s planned course.

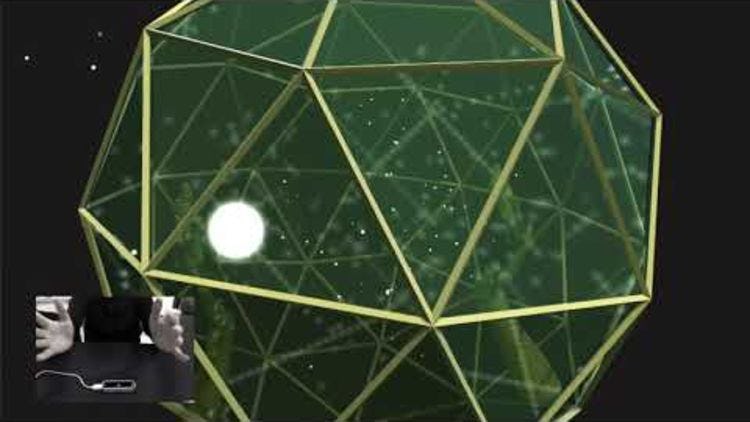

Her own art began evolving, and by senior year, she had two pieces of work that drew attention. One was presented at Vault Allure, a music and art festival in Jersey City sponsored by Nokia Bells Labs. A sensor resting on the table tracked users’ hand gestures, allowing them to manipulate a virtual sculpture, and as the sphere on screen expanded and contracted, the machine’s audio output fluctuated.

Her project titled “Bicycling Through Childhood” also engrossed the crowd at Stevens’ senior visual arts and technology exhibition. After straddling a bike and strapping on a virtual reality headset, users began pedaling through a rendered neighborhood. Some were enthralled, others became a bit dizzy, but nevertheless, everyone experienced what McPhatter describes as “embodiment,” an intense synchronization between the art and its viewers. McPhatter knew the project would push her technical limits, but her professors encouraged her to keep moving forward, knowing her drive would carry her over any hurdles.

This lesson sticks with McPhatter to this day. “I’m definitely one to have an idea, then figure out how to do it afterwards,” says McPhatter. “I try and be as ambitious as possible, because a lot of what drives me to want to do these projects is just pure passion.”

— Connor Durkin