Hurricanes Harvey and Irma: Lessons Learned, Cautions for New York & New Jersey

Stevens Institute of Technology experts analyze what went wrong in Houston, and how New York and New Jersey should prepare for the next catastrophic storm

The recent destruction wrought by Hurricane Harvey in Texas, which claimed more than 60 lives and caused nearly $200 billion in estimated property damage, was not entirely preventable.

But it was likely made much worse by decades of poor urban planning.

Now, as urban areas worldwide inspect both the Houston damage reports and their own infrastructures and emergency-management plans — while keeping a wary eye on Hurricane Irma as it churns west across the Atlantic — Stevens Institute of Technology is providing planning, operational forecasting and engineering expertise to help coastal cities prepare for the worst.

"A perfect recipe for disaster"

Even though Houston sits above sea level, its topography invites catastrophe when a storm makes a direct hit, explains Stevens professor and Davidson Laboratory director Alan Blumberg, a leading global expert on storm-surge flooding.

"The topography of Houston played a key role," says Blumberg. "During heavy rainfall such as occurred during Harvey, water level rises and it needs someplace to go. Because Houston's topography is so flat, it didn't have anywhere to go."

That problem was exacerbated by a boom of recent development in southeast Texas, much of it in known flood zones.

"Since 2010 more than 9,000 buildings have been constructed in a known 100-year flood plain in Houston," points out Stevens senior research engineer Firas Saleh, another expert in flood modeling who has helped cities such as Philadelphia engineer for disasters. "Approximately 30 percent of the city's wetlands were converted entirely to parking lots and buildings. That is just massive building in flood-prone zones, and — combined with aging infrastructure and rising seas — you have a perfect recipe for disaster, which is what we saw with Harvey."

"The bayous and other natural water-channeling areas are largely cemented and built-over now," adds Blumberg. "Once you do that, water that used to go into a low-lying area or bayou can't get there anymore. It can only rise much higher and push inland."

Saleh says traditional design practices for drainage systems have long proceeded with the assumption of "climate stationarity," meaning the frequency and magnitude of weather patterns are assumed to remain similar in the future. But new factors, such as climate change, would alter those processes, leading to more extreme temperatures, rising sea levels, changing precipitation patterns, and changing frequency and severity of storms.

Those environmental stressors must now be considered when engineering and retrofitting communities, Saleh says, while there is still time.

It can happen here — again

The New York City metropolitan region has a closely vested interest in questions like these.

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy proved that the worst-case storm can strike New York City with a direct hit. Sandy brought twelve-foot flood tides, killed more than 200, caused approximately $70 billion in property damage to the Eastern Seaboard and required several years' work to rebuild beaches, homes and communities.

Stevens' resiliency experts say it can, and quite possibly will, happen again.

"As climate changes," notes Blumberg, "the weather gets warmer and the ocean gets warmer. Warmer ocean water leads to stronger hurricanes."

"And those effects can multiply," adds Saleh. "What if the next storm in the metropolitan New York region is a 'Sandrine' — a combination of massive, Sandy-like storm surges and heavy, Irene-like rainfall? Nobody is quite prepared for that."

While it's not possible to prevent catastrophic natural disasters like superstorms from happening, Saleh notes that successful mitigation strategies may prevent natural disasters from becoming human tragedies.

Blumberg suggests that urban planners consider innovative engineering techniques and adaptive strategies that account for non-stationary climate conditions to increase the resilience of urban coastal cities. Wetlands and oyster reefs, for example, can act to reduce the impact of flood events — but, to do so, they must cover large expanses to be effective.

"Innovative preparation will be critical as cities are increasingly facing threats from hurricanes and tropical storms," he notes. "This is a problem we have all created, and we will all need to work together to solve it — quickly."

To that end, Stevens is already working closely with the New York City Mayor's Office, the Port Authority of New York/New Jersey, NJ Transit and cities such as Jersey City to forecast and prepare for floods driven by storms and sea level rise.

"Those forecasts are driven by a dedicated supercomputer and integrate the latest Stevens-created mathematical and hydrological models — models considered so accurate that they are currently promoted by both the National Weather Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)," notes Blumberg. "We also have water level observations coming in from 150 locations every six minutes."

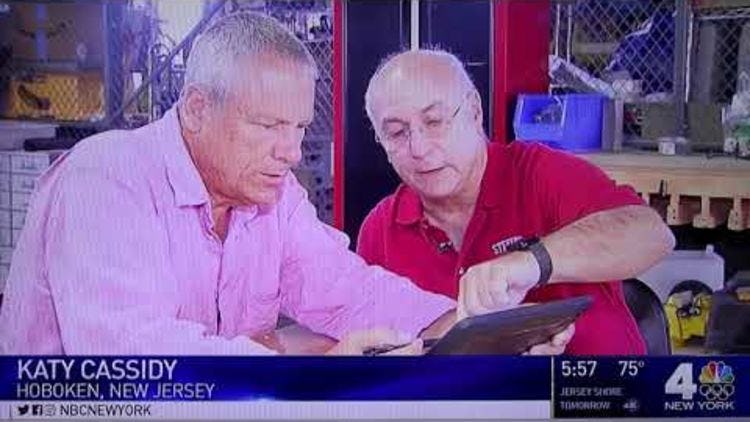

Professor Alan Blumberg Discusses FlooD Forecasting ON FOXNEWS

To learn more about Stevens' flood forecasting and resiliency planning, or to request media availability with faculty experts, contact Kat Cutler, Manager of Media Relations, at 201.216.5139 or 603.799.8076 or via email at [email protected].