A Stevens Professor’s Dedication Rescues Students’ Lab Experience from COVID-19

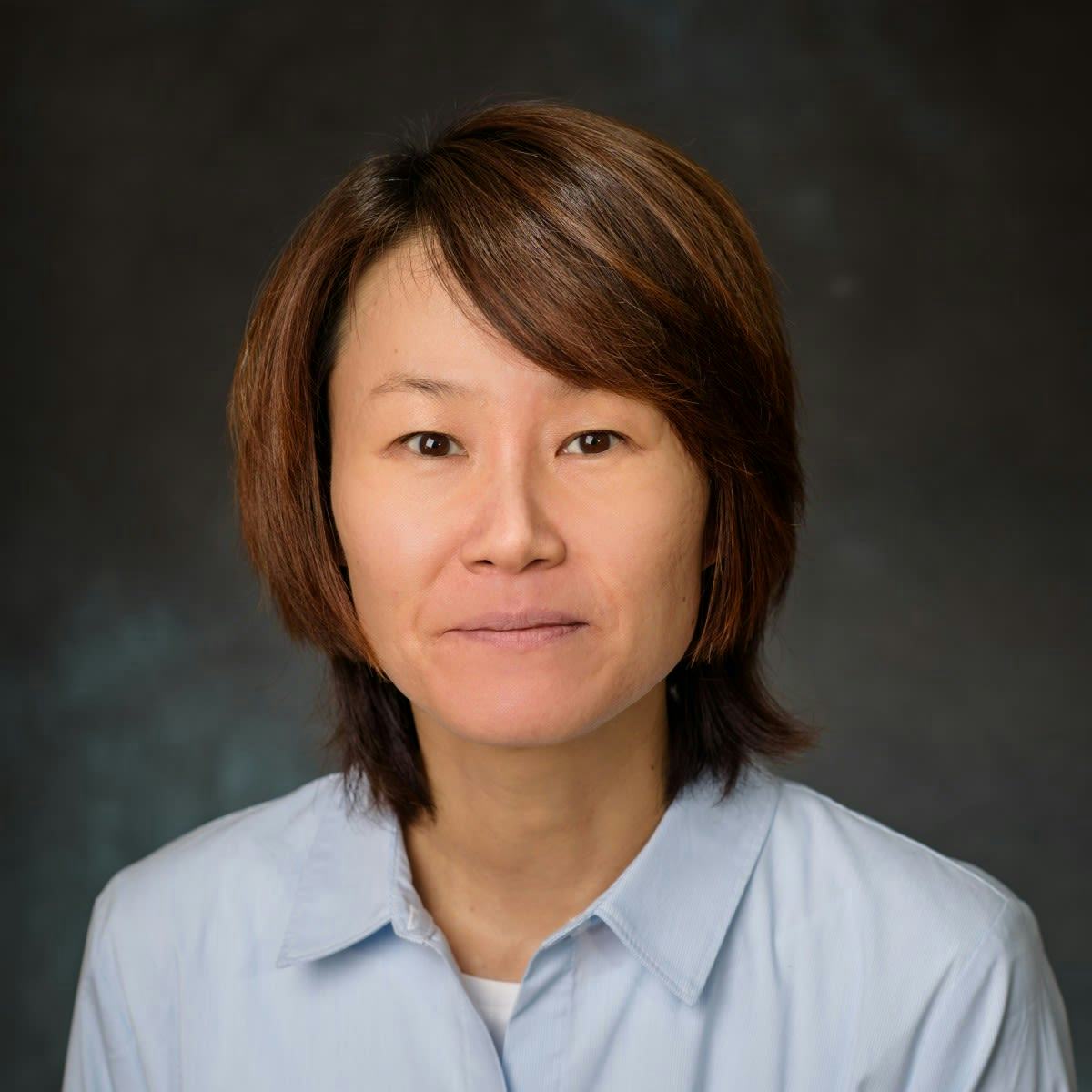

Professor Faith Kim prioritizes student centricity and hands-on experience

Stevens is a university known for its hands-on labs and real world projects that give its students a leg-up in experience when they enter the job market, but with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, universities across the world were forced to adapt to a new style of learning. Maintaining the integral hands-on aspect of the student experience during a time of social distancing was of the utmost importance to Faith Kim, professor in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, who went above and beyond to ensure her lab students still received the value of hands-on learning and would be prepared for their future.

“There is a gap between the experience of virtual versus in person,” Kim explained. “A virtual lab can be taught almost the same as an actual lab. We show them step-by-step what they would actually do if they were there in person. They see the feasible results that they can then analyze virtually.”

“But there are basic techniques they learn in the physical lab—for example, pipetting. It’s very simple and they do it repeatedly. In person, they actually handle pipetting regularly. They can do it at the end of the semester and can start the research lab right away. Virtual students watch pipetting over and over, but they cannot do pipetting,” she said. “Even though it was challenging, I chose to go with hybrid.”

Kim was convinced that in-person lab time was vital to students’ future success, but the realities and dangers of COVID-19 necessitated adherence to strict safety precautions. With nearly 500 enrolled in her lab, facilitating these protocols was going to be a challenge–but one that Kim was determined to overcome.

Preparing in a pandemic

With Stevens’ emphasis on student-centricity as her primary motivation, Kim’s first dilemma was determining how to both deliver a high-caliber lab experience while also ensuring the safety of everyone involved.

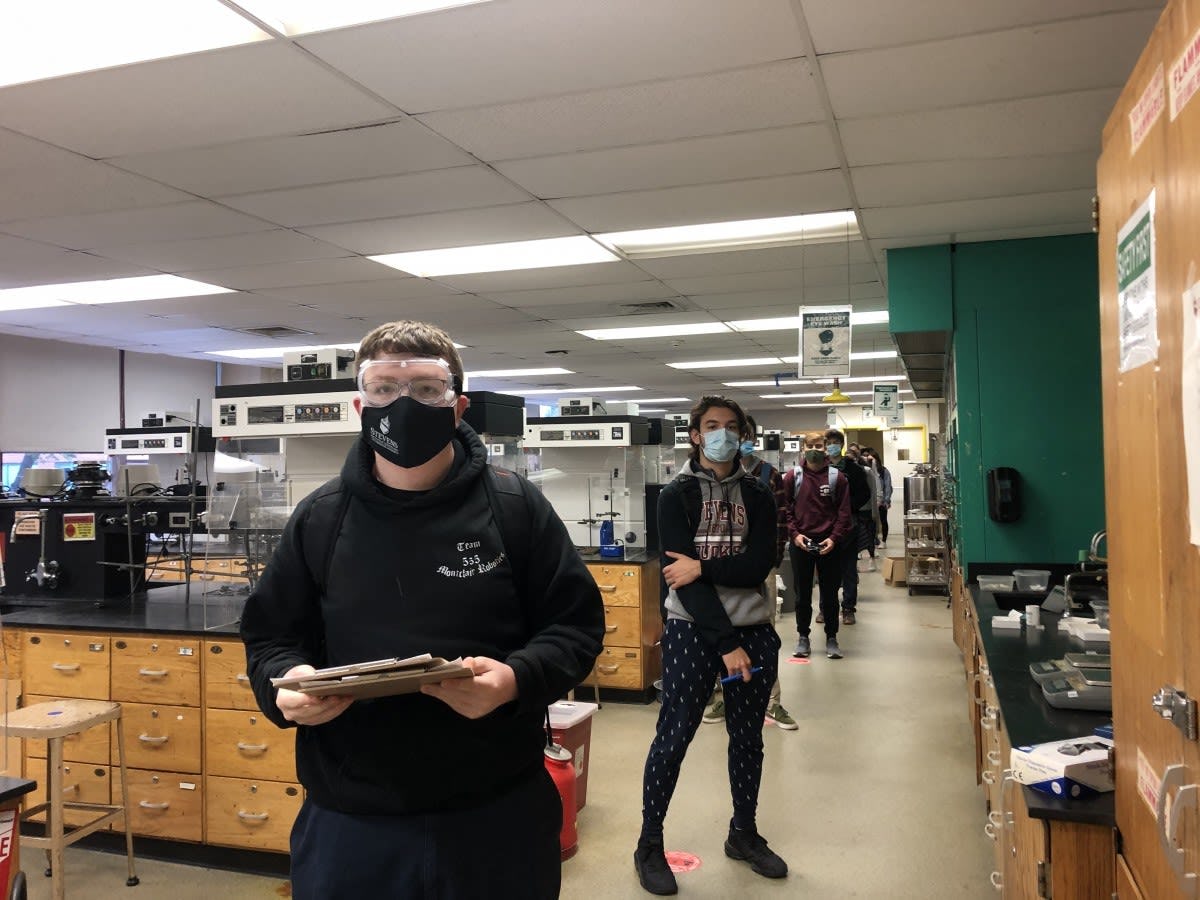

Each lab course had 60 enrollees, but in order to adhere to social distancing protocols they could only accommodate 36 at a time in person due to space and equipment limitations. In past semesters, they typically worked in pairs—but they now had to work individually, meaning extra equipment needed to be ordered in order to accommodate additional lab stations.

“We only had fifteen top-loading balances,” Kim recalled. “We placed an urgent purchase request for more. We were supposed to start after Labor Day, but we didn’t get the balances on time—even though we placed the order a month ahead. I had to create a back-up plan for running the lab without them. I asked the TAs to weigh out 400 samples for students! They weighed samples for two-to-three days.”

When the balances eventually did arrive, Kim had to find time to pick up the delivery herself. “It was a huge order of chemicals and extra equipment for almost 500 students,” Kim reflected with a laugh. “I had 12 sections a week, which is 36 hours. I was running 12 online sections. Not only that, after every section we had a cleaning crew come in to sanitize the lab and bench sections. I didn’t have much of a free window. I had to bring my car to the receiving department, load up the supplies, and come back. It was crazy.”

Success in safety

Kim strategized ways to provide her students with the opportunity for in-person labs, but the protection measures required to create a safe lab environment were not always easy. She wanted to be flexible and sensitive to concerns and it was important to her that they never felt pressured to participate.

“I told them it was their choice,” she said. “They could start with in-person, which is what I preferred, but they could switch to virtual any time if they felt uncomfortable. If they didn’t feel comfortable coming, for any reason, we accepted it. They had the option to switch to online from the very beginning.”

Much to Kim’s delight, students were very receptive. “Even though they felt uncomfortable in the setting they had to endure, everyone was accepting.”

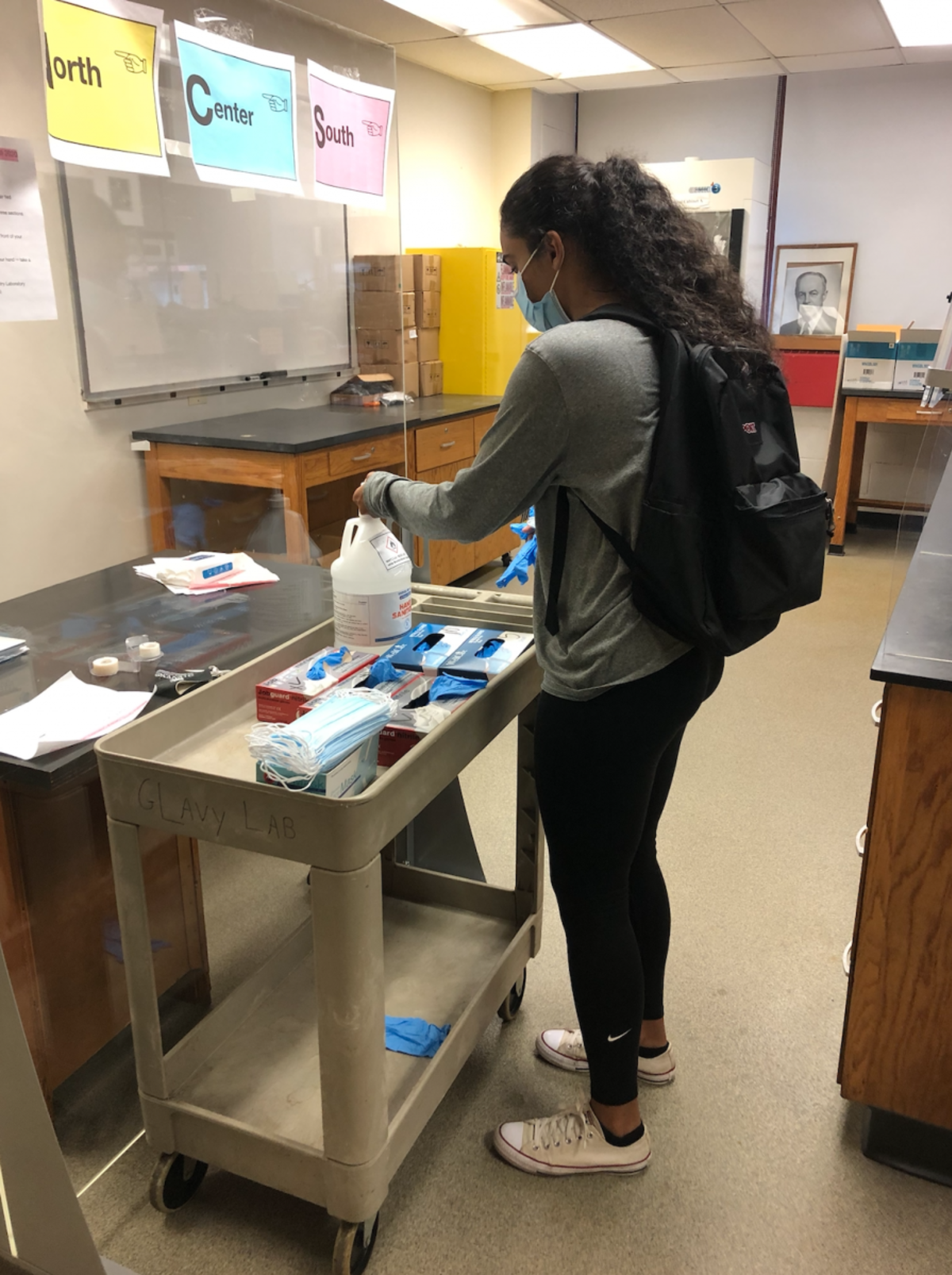

Each lab session began with the arduous process of donning personal protective equipment (PPE.) Prior to entering the lab, students were directed to sanitize their hands and put on gloves. Then, they were given individual disposable masks in order to avoid splashing chemicals or vapor on their personal face masks. After entering the lab, they couldn’t remove their masks or gloves until the lab session was finished. Additionally, they exited from a different location than they entered, so as not to have any overlap.

“We also used one big plexiglass where we were accepting students to protect the student aids who helped check them in,” Kim said.

While the lab’s 16 windows—which Kim would arrive early to open—helped with airflow, they did present challenges with temperature stability. At the beginning of the semester, the opened windows reduced the effectiveness of the air conditioning. Toward the end of the semester, they faced the opposite problem: the opened windows caused the lab to be cold.

“When they used the Bunsen burner, it was hot,” Kim said. “Since students used chemical splash goggles, they would get foggy. They had to wipe their goggles a few times during the lab. So: Bunsen burner and face mask and fogging goggles. They were supposed to cover their skin as much as possible so they also had to wear long sleeves and long pants.”

While participants were only in the lab for a maximum of three hours, Kim herself was there all day long.

“Since we had back-to-back sections, the cleaning crew was spreading vapor throughout the entire lab section,” she said. “I got headaches from the vapor, even with good air circulation.”

Due to ongoing research and evolving findings on COVID-19, it was unclear at the time whether those precautions would be enough to minimize the spread of the virus.

“At the beginning, we didn’t know if our safety precautions would be sufficient, so I wasn’t sure if the setting would work or not,” Kim admitted. “I was very anxious.”

As it would turn out, they weren’t taking all these precautions in vain. Stevens conducted weekly COVID-19 testing, and from September through October the infection rate was very low. The safety protocols were actually working, making it safe to continue to conduct labs in person. It was more challenging and uncomfortable than running a traditional lab, but their efforts were successful.

“Full contact tracing was key for staying open. Based on contact tracing, there was no spreading occurring in our lab. That was the motivation to keep going,” Kim said. “The infection rate on campus was lower than outside, which was really encouraging. Not only was it safe, but it was safer for students to stay on campus rather than go outside. It was really challenging but really rewarding, in the end.”

A worthwhile endeavor

Although the fall 2020 semester presented obstacles to running a physical lab space unlike any she had ever encountered, Kim said she would do it all again if given the same choice. The rewards exceeded her expectations.

For one, she learned that she can run a virtual lab in emergency situations, something that, prior to the pandemic, she had not seriously considered. “Now I have all the material I need as a back-up, whenever we have a snow day, I don’t have to worry. Every semester, I had to arrange make-up sessions for students who missed their labs. Now that I have the material, I can always run a virtual make-up.”

There are also more concrete rewards that will enhance the learning environment for future cohorts. Kim is particularly pleased with having obtained extra lab equipment.

“Usually students share balances and now I have balances for everyone,” she said. “Even when we come back in person, no one will have to wait.”

Overall, she is glad she took the risk because it meant she was able to deliver on Stevens’ promise to provide students with real-world, hands-on educational opportunities that many students at other universities likely missed out on.

While everyone is hopeful for a return to some semblance of normalcy in the near future, Kim is grateful to have been able to make the most of an unfortunate situation. Because for her, it’s about the students and their futures.

“We started with 80% enrollment in-person and ended with about 73%,” Kim said. “Those students still got a little in-person experience. I was happy. The challenges were worth it.”

Learn more about chemistry and chemical biology at Stevens: