When Preparing for Hurricanes Amidst a Pandemic, Knowledge Is Power

As experts predict one of the most active Atlantic hurricane seasons in history against the backdrop of a pandemic, the Stevens Flood Advisory System is keeping the data flowing so emergency response officials can plan to keep everyone safe

If the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season is anywhere near as severe as experts are predicting, we’re going to need to ramp up emergency preparations, a process that will be significantly more challenging given the social distancing measures enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Flood Advisory System at Stevens Institute of Technology is on the forefront to provide accurate and reliable information that can help in saving lives and reducing economic losses.

What will the 2020 hurricane season look like?

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is projecting that the 2020 hurricane season, lasting from June 1 to November 30, will yield between 13 and 19 named storms. When a tropical storm’s wind speeds top 39 miles an hour it earns a name, and when it passes 74 miles per hour, it reaches hurricane status. The forecast calls for three to six major hurricanes classified as category 3, 4, or 5 with winds above 111 miles per hour. Such major hurricanes have the potential to wreak devastating damage.

Gearing up to manage emergency preparedness in anticipation of a barrage of hurricanes is difficult enough—how will government agencies and public health leaders manage in the midst of a pandemic?

Keeping current with storm surge predictions

The first step in preparing for any natural disaster is information-gathering, to amass and understand as much as possible about the situation.

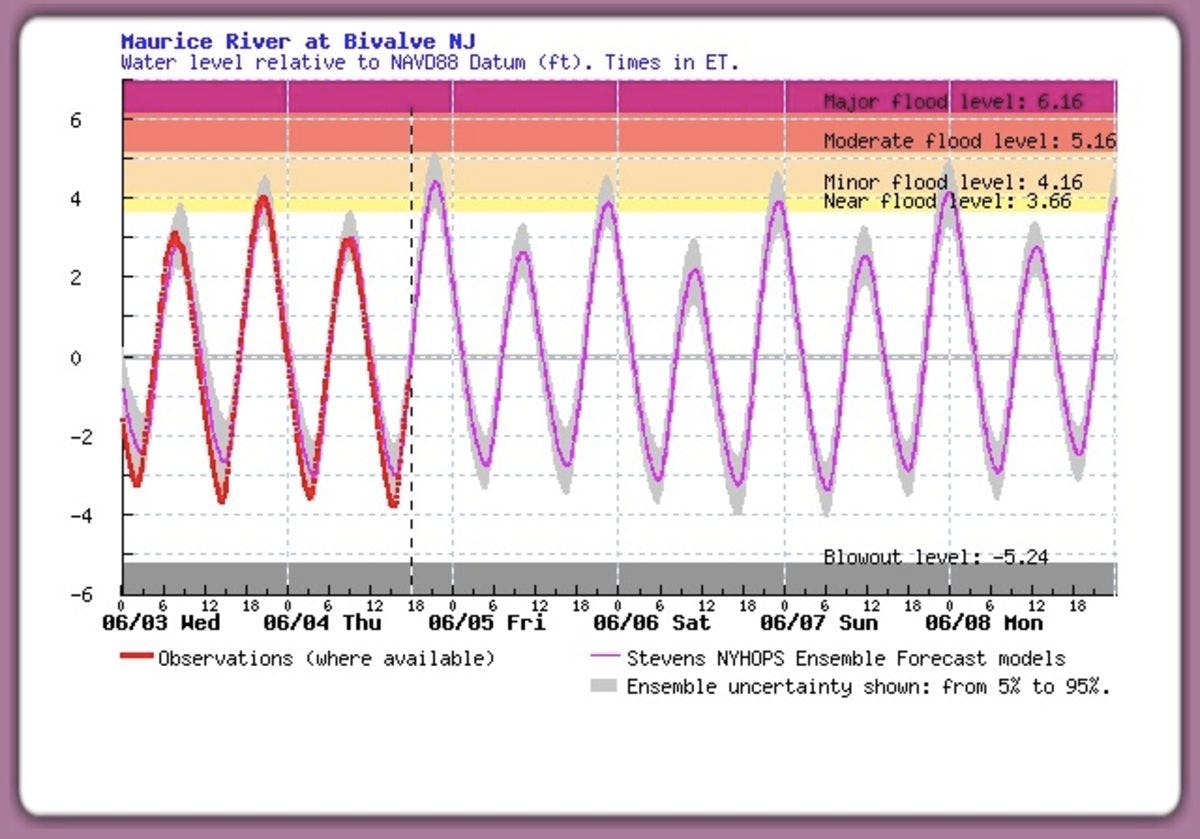

At Stevens Institute of Technology, researchers in the Davidson Laboratory have developed the Stevens Flood Advisory System, which has evolved as the leading flood forecasting system for its neighbors in the New York City metropolitan region and parts of the Jersey Shore. This world-class forecasting system runs 24 hours a day, seven days a week, every day of the year; and directly provides a four-day prediction of local storm surges and river water levels.

“With or without a pandemic, our storm surge predictions support emergency managers involved in dynamic planning toward mitigating the impact of those events,” said Muhammad Hajj, chair of the Department of Civil, Environmental, and Ocean Engineering (CEOE) and director of Davidson Laboratory at Stevens. “But clearly, recognizing the additional challenges posed by COVID-19 on managing evacuations and sheltering and deploying emergency workers, it is important from our perspective to make sure that our predictions are as accurate as they can be.”

Improving that accuracy is an ongoing mandate for the Stevens Flood Advisory System. One of the most useful advances has occurred in the eight years since Hurricane Sandy ravaged 24 U.S. states, including New York and New Jersey.

“Since 2012, we’ve pushed our prediction window from 48 to 102 hours,” said Jon Miller, research associate professor and coastal engineer at Stevens. “We’ve expanded our resources from primarily using the meteorological forecast from the National Weather Service, to running our model using ensembles of more than 120 forecasts from the U.S., Canada, and Europe.”

Branching out has allowed the Stevens Flood Advisory System team to predict storm surges more accurately and earlier, and to better understand which models work best in different conditions. Hajj noted, “As we transition our computations to the cloud, we will be able to perform more dynamic modeling where the required ensemble runs from different meteorological forecasts; the frequency of runs, and the spatial resolution would be varied depending on storm characteristics to yield more accurate forecasts. The idea is to allow for more certainty on the impact of storm surge—will it reach critical electrical infrastructure, power grids, or facilities where ambulances and other critical pieces of equipment are housed? Will it cause disruptions to the operation of ports? Accurate predictions can make a difference in supporting decision-makers and their planning.”

Miller added, “The cloud will enhance our computational capabilities—to run forecasts faster or perhaps more frequently—while also providing resilience; ensuring the forecasts continue to run should a storm hit Hoboken or Stevens and impact power and communications locally.”

Spreading the word—but not spreading the virus

Since traditional emergency shelters such as schools and other large buildings will be hard-pressed to sustain the social distancing measures implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, that kind of accuracy and advance warning becomes even more critical for public health experts.

Since Hurricane Sandy, Miller has worked with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the Port Authority to help inform decisions on improving resilience, planning, and communications related to flooding. He’s well aware of the additional challenges presented by the coronavirus.

“It’s likely there would be a hesitancy to evacuate because of fears related to the coronavirus,” Miller said. “But the danger of being swept away in a storm is likely going to be higher than potential exposure to the virus. Convincing people that evacuating is the right thing to do is a difficult problem that officials will have to wrestle with and overcome. It is interesting that one of the learnings that came out of a NOAA study was that people are more ready to believe their local chief of police or mayor as opposed to state or federal government representatives, so that’s something officials might want to keep in mind.”

The team at Stevens is doing its part to ensure communications are not only accurate, but also easy to understand and believe.

“Having been through Hurricane Sandy and considered why people might be reluctant to listen to evacuation advice, we’ve reassessed everything—from heavy-duty engineering considerations to communications,” Miller said. “Even our site’s graphics are clearer than they were, which we hope will add clarity and improve people’s confidence in our forecasts—and lead to better decision-making and improved safety.”

But getting people in potentially dangerous areas to agree to evacuate during the pandemic is only the beginning of the challenge.

“Many people are in tough economic situations, so even if they want to evacuate, they might not be able to afford to drive 200 or even 100 miles away, or to stay in hotel for a few days or weeks,” said Reza Marsooli, assistant professor, civil, environmental, and ocean engineering. “There will need to be enough shelters to safely accommodate mass evacuations while still keeping protocols such as social distancing to prevent the spread of the virus. There will need to be enough civilian volunteers willing and able to overcome their fear of the virus and work alongside the government agencies to help. As we study coastal flood hazards and how climate changes impact those hazards, especially this year with the active hurricane season being forecast, we’re always thinking about how emergency preparedness can be handled.”

Dealing with the waves of the future

Even beyond the pandemic and the dire predictions for the current hurricane season, experts predict that climate change may continue to present challenges to the general population as well as government officials and other emergency planners.

“Research has shown that hurricanes would get stronger and potentially increase in frequency, and we may see a larger number of catastrophic hurricanes making landfall in the U.S.,” Marsooli said. “Flood hazard assessments have been typically based on historical storm and rainfall events, but it’s also important to incorporate any effects of climate change. Past extreme events will not be extreme events in the future; they will be much more normal events. We’ve seen it recently with the dams that failed in central Michigan, and the ones that may fail in Virginia, all because of changing patterns in extreme rainfall events that designers did not factor into the construction. The danger is to take no action and keep relying on information from past events. People need to maintain and design for the future.”

Learn more about environmental engineering at Stevens: