Stevens research team uses vetiver grass to decontaminate soil and water, naturally

Lead dust from house paints, an aging water supply infrastructure and other sources have been linked to declines in IQ in exposed children as well as a host of neurological disorders and birth defects. The U.S. banned lead from paints in 1978 and from most plumbing fixtures in 1986, yet much remains in the built urban environment.

Most recently, news headlines have focused on the crises of elevated lead levels in the water supply in places such as Flint, Michigan, and Newark, New Jersey. But soils and plants in urban neighborhoods — in people’s own backyards — also pose an ongoing threat.

Deterioration of exterior lead-based paint in older homes, industrial pollution and the use of lead-based gasoline have contributed to the contamination of soil, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). This contaminated dirt from the outside can make it into people’s houses, as they track in lead dust from the backyard on their shoes. This problem is most critical for young children, from birth to age six, because exposure to lead can be particularly harmful during this time of rapid brain development.

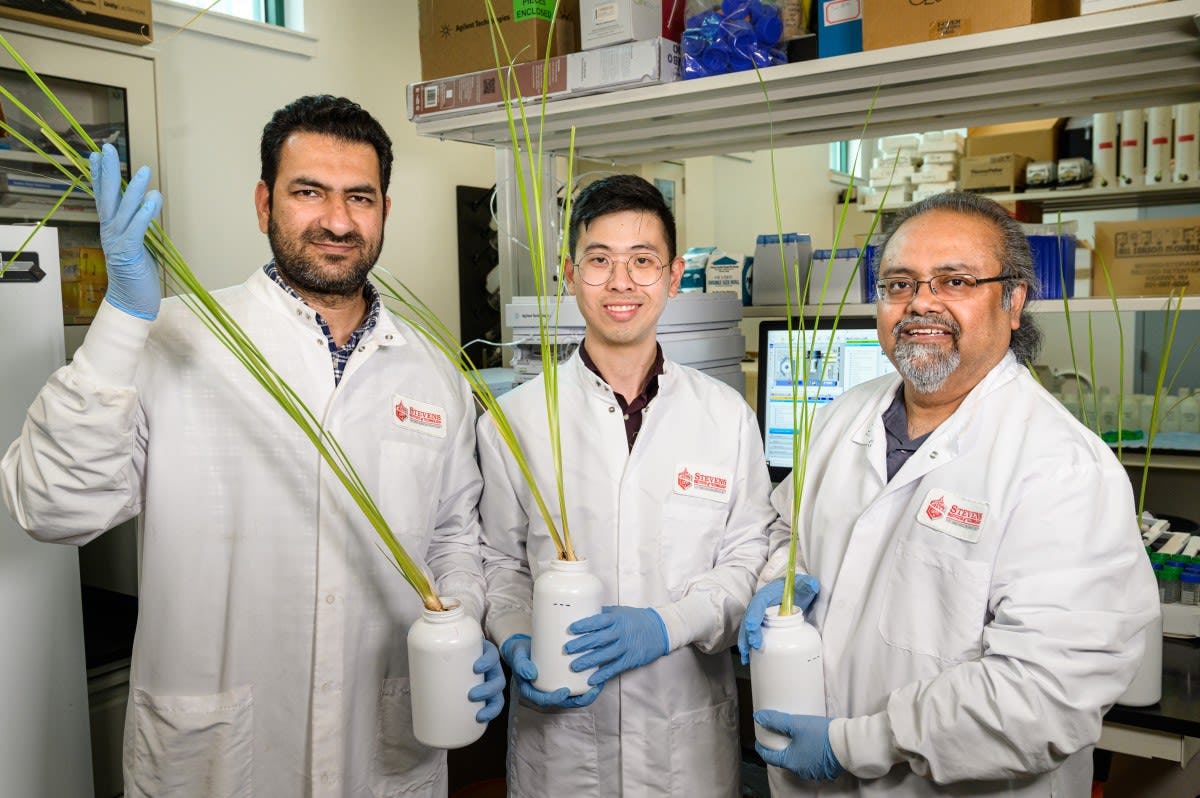

When it comes to abating the lead crisis in some communities, progress has been slow and solutions cost-prohibitive to residents. But Stevens environmental engineering professor Dibyendu Sarkar and his team are working on one affordable green solution: vetiver, a fast-growing bunchgrass from India with long, dense root systems that absorb significant quantities of lead and other heavy metals from contaminated soil with the help of biodegradable green chemicals. With a $500,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) — the third phase of a $1.4 million grant that dates back to 2004 — Sarkar and his team are working on two pilot sites in Jersey City, New Jersey, and two in San Antonio, Texas, where they have planted vetiver in residential backyards contaminated with lead. The early results have been encouraging.

In one field site in Jersey City, for example, where the team has been working since 2018, the soil lead level decreased from 750 mg/kg to 460 mg/kg, according to Sarkar. (The safe/ permissible lead level in residential soils set by the EPA is 400 mg/kg.) At the second Jersey City site, the lead level decreased from 704 mg/kg to 574 mg/kg. And in San Antonio where Stevens is collaborating with Michigan Technological University, one site saw a decrease from 445 mg/kg to 396 mg/kg. Sarkar and his team were growing a new crop of vetiver at a greenhouse earlier this year and hoped to plant a new crop in Jersey City this spring, though this may be postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic.

“We are reducing pollution in big cities,” Sarkar says. “I think that we have made progress. We still have a lot to do.” Sarkar, who is founding director of the Sustainability Management Program at Stevens, pointed out that this solution, though not a silver bullet, is affordable, ecologically sustainable and is being developed so that it’s simple enough for a gardener to use.

“If it’s technologically complicated, people cannot use it. Our job is to come up with green technologies that can be easily implemented.”

The process works like this. Vetiver plant are planted in the soils in the backyards of the residential pilot sites. The soil is then treated with a green biodegradable chemical called EDDS (ethylenediamine-N, N’-disuccinic acid), which makes the lead in the soil soluble, enabling the vetiver to absorb it. The vetiver grows and is harvested periodically, thus removing the lead. In Jersey City, the vetiver is harvested, and new grasses are replanted each spring. In San Antonio where winter is mild, grasses do not need to be replanted.

In a separate project, vetiver has also been tested by Sarkar’s team to remove nutrients and antibiotics from wastewater. These substances pass through wastewater treatment systems unabated and percolate into surface and groundwater. Prolonged exposure to water suffused with antibiotics may promote antimicrobial resistance in humans.

Sarkar’s team performed a greenhouse test on tanks filled with municipal wastewater, spiked with two common antibiotics — ciprofloxacin and tetracycline. The vetiver’s massive root system removed nearly all antibiotics — along with excess nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorous — within as little as two weeks, the team found. The vetiver is later burned into biochar and the antibiotics destroyed.

Another vetiver partner: The Town of Secaucus, New Jersey. Sarkar’s research team, with funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, will test a floating water treatment platform, filled with vetiver grass, on top of a storm water retention basin, in an industrial area of town next year. Indeed, when it comes to the capabilities of vetiver, Sarkar says that his team is “just scratching the surface.”

Students and researchers working on the vetiver projects appreciated this opportunity to find solutions to vexing environmental problems while getting to see the results of their work in a relatively short period of time. “The most satisfying thing is how the lead concentration is going down in the soil,” says Virinder Sidhu, a postdoctoral fellow with the Department of Civil, Environmental and Ocean Engineering. “You can see it in real time. And this is much more sustainable and less destructive.”

These projects have been deeply rewarding, Sarkar says. His HUD-funded project, in particular, is trying to right an environmental justice problem, he points out, where children in poor neighborhoods suffer. He is also helping young researchers to come up with solutions that benefit all of society.

“We should train students that development comes at a cost — a cost to the environment. We are actually walking the walk of sustainability.”

The Hugo Neu Corporation Sustainability Seminar Series — which includes a free live webcast and is organized by Stevens’ Sustainability Management Program — continues this fall, with experts speaking on important sustainability issues. Past lectures are also available to be viewed online.