Stevens Investigating Acoustic Soundprint Technology to Detect 'Murder Hornets’

Researchers working on system that can ID the invasive hornet pest by its unique buzz

The Asian giant hornet — two inches long, with a nasty habit of stinging humans and decapitating native honeybees (which are vital to agriculture and horticulture) — has landed in North America.

Dubbed the "murder hornet" by The New York Times, the hornet has spread widely in Europe over the past decade and recently been identified in Washington state and western Canada likely after hitching a cargo ride from Asia. Eradicating the pest won't be easy, as its preferred habitat (burrows and hollowed logs in the deep woods) makes its hives near-impossible to locate.

And with nearly 20,000 cargo containers arriving daily at U.S. ports during typical times (pre COVID-19, in other words) — only 2% of which are typically opened and inspected — there's potential for additional invasive species to arrive in the future.

Now Stevens Institute of Technology researchers suggest a new way to find and neutralize the invaders.

Unique buzzing could lead scientists to the hornets

The passive acoustic technology, originally dubbed Stevens Passive Acoustic Detection System (SPADES), was first developed a decade ago to help detect and locate divers and underwater and surface vessels by their unique sounds.

"Later the system was extended to aircraft and drone detection, and more recently fine-tuned to inspect wood-packing materials in shipments arriving at ports of entry for insects and to detect destructive forest pests such as the Asian long-horned beetle. That system provides insect detection in the woods via specially rigged boxes wirelessly transmitting data," notes Hady Salloum, director of the university's Sensor Technology & Applied Research (STAR) Center.

To attack the hornet ID challenge, the STAR Center research team is currently creating new sound libraries of the murder hornets, as well as native bee species, to integrate algorithmically with the existing detection system.

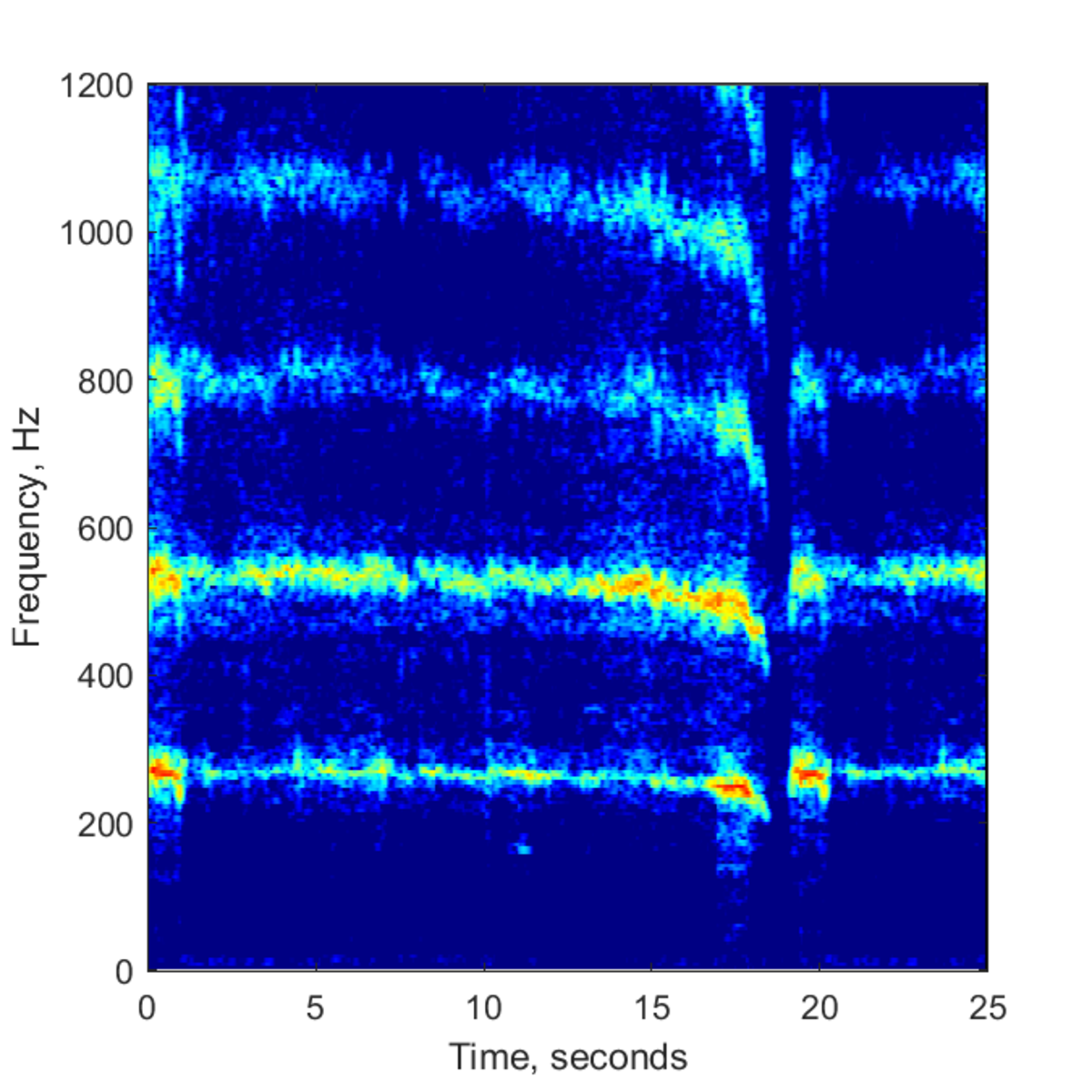

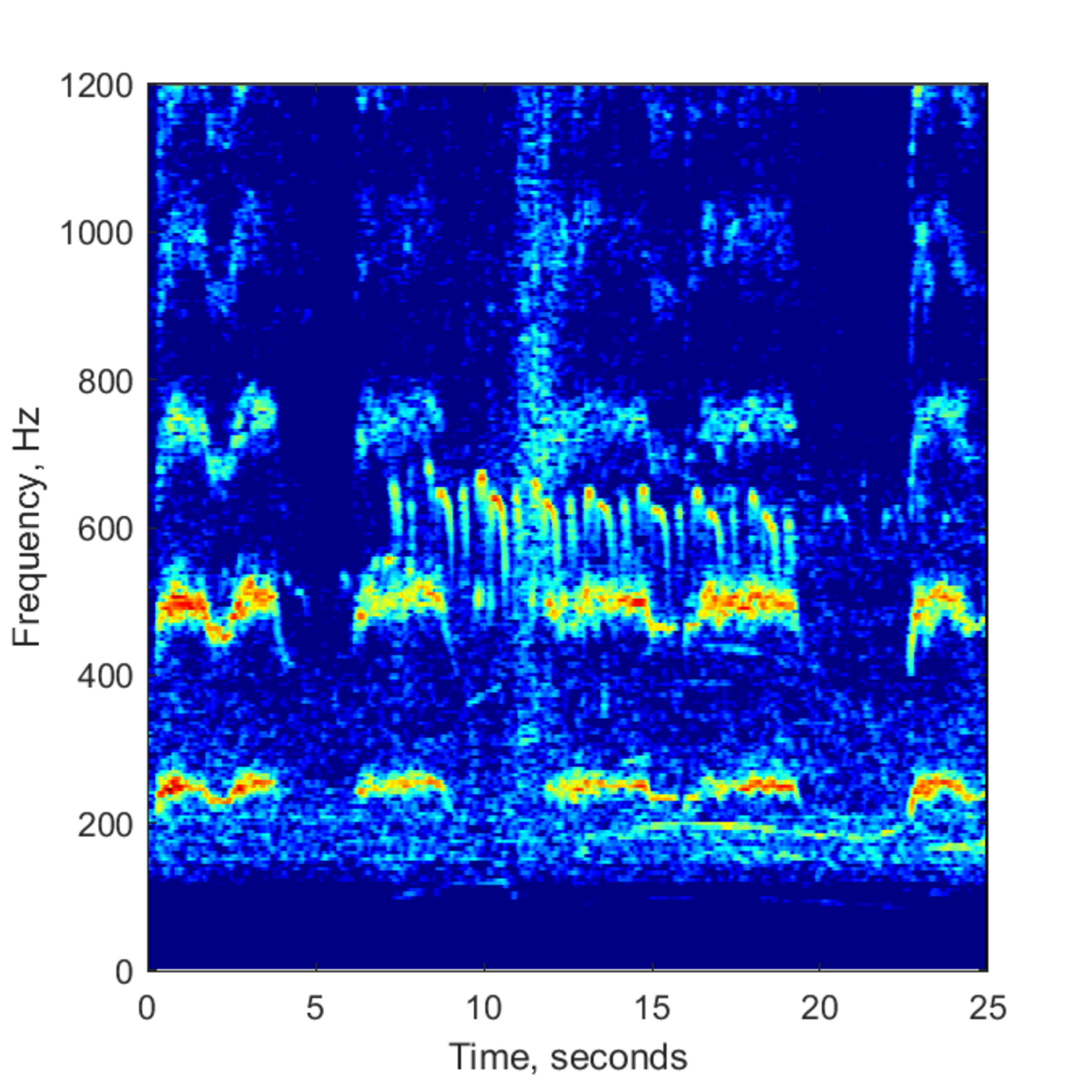

"When you compare the flight sounds of the Asian hornet with those of the most common honeybees in North America, there are definite similarities in the sound frequencies," explains Alexander Sutin, a Stevens research professor working on the technology. "But there are also differences in the variation of those sounds that make the sounds audibly different. This may reflect differences in their flight patterns.

"We can catch the sound using our microphone array systems; separate the sounds; classify them; and make highly accurate attributions in the field. This can benefit us in the fight against invasive species."

The team has already demonstrated differences in the acoustic signatures of the Asian giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia) and the European honeybee (Apis mellifera).

"Due to COVID-19, we obviously can't test this technology in the field quite yet, but we are keeping our acoustic system ready for tests," notes Salloum. "We will be seeking interested private and public partners to collaborate with. In the past, we have worked with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, for example, who were quite helpful in our forest-pest research.

The team is also considering a second solution to the challenge of locating the pests, adds Salloum: attaching a small radio frequency beacon tag to individual hornets to track them back to remote nests. Stevens researchers previously developed and built miniature long-range trackers, then demonstrated their usefulness for accurate drone tracking; other researchers have demonstrated that bees can indeed be fitted to carry tags in flight.

"A similar technology could be another avenue for potential investigation," concludes Salloum. "I think everyone in North America wants to ensure these murder hornets don't spread more widely."

Sonographic comparison of flying Asian giant hornet and European honeybee