A Smarter, Simpler Baggage Transfer Solution: Stevens Students Receive High Honors in Airport Design Competition

The Transtag system increases percentage of on-time priority bags and reduces costs, according to model

A family waits to board their plane. The children are excited. Their parents hope for a smooth vacation. Sitting in the same airport lounge are two entrepreneurs preparing for a meeting that can help skyrocket their startup to new heights.

All is well; that is, until they learn that their flight is delayed.

Unfortunately, scenarios like these occur far too often, and airports are scrambling for solutions.

Enter four Engineering Management students who graduated from the School of Systems and Enterprises (SSE) at Stevens Institute Technology in 2017: Yasha Binyamin, Owen Burke, John Mawad and Evan Sandford.

According to the team, missing baggage is to blame for a good number of flight delays in the U.S. And 45 percent to 49 percent of the bags that fail to make it to their correct destinations go missing between transfer flights.

The Stevens team set out to design a system to address one of the biggest underlying causes of missing luggage: a baggage transfer system which has remained largely the same for the last 40 years. They kept their solution, Transtag, simple to offer airlines an affordable way to improve the baggage transfer aspect of the system.

Smart system design, award winning solution

The Transtag system was recently recognized by the Transportation Research Board’s (TRB) Airport Cooperative Research Program (ACRP) for its innovative design and awarded third place honors in the Airport Operation and Maintenance category of the ACRP University Design Competition for Addressing Airport Needs. Sponsored by the Transportation Research Board, the aim of the Competition is to spur innovative thinking in solving some of today’s toughest airport systems challenges, and give students valuable educational experiences and quality exposure to careers in aviation and airport operations.

“This achievement in this competition means a lot to me,” says Mawad, who has been working in the aviation industry for the past 3 years while attending Stevens. “Third place in a national competition is something we are very ecstatic about.”

The opportunity provided the team a glimpse of success in real word problem-solving. “We are third in the entire country,” exclaims Sandford. “I now have a lot more confidence in myself.”

“This is the fourth time that a team of Stevens Engineering Management students receive high honors in this national design competition,” says Stevens Professor Eirik Hole. “Their achievement is a result of their relentless enthusiasm, great team dynamics, and that they looked at the whole baggage handling process from a systems perspective. That enabled them to identify a leverage point and they had the creativity to come up with very simple, pragmatic solution.”

Simplicity in systems design is key to improving baggage handling processes

Eight out of every 1,000 airline passengers discover that their bags are missing shortly after arriving at their destinations – approximately 28 million bags per year – according to the team’s report. The consequences for airlines include poor customer service reputation and loss of business. Add the fact that each missing bag has the potential of costing an airline thousands of dollars in reimbursement fees per customer (not including initial bag checking fees) and it becomes clear that improving baggage handling processes is a business imperative for airports across the U.S.

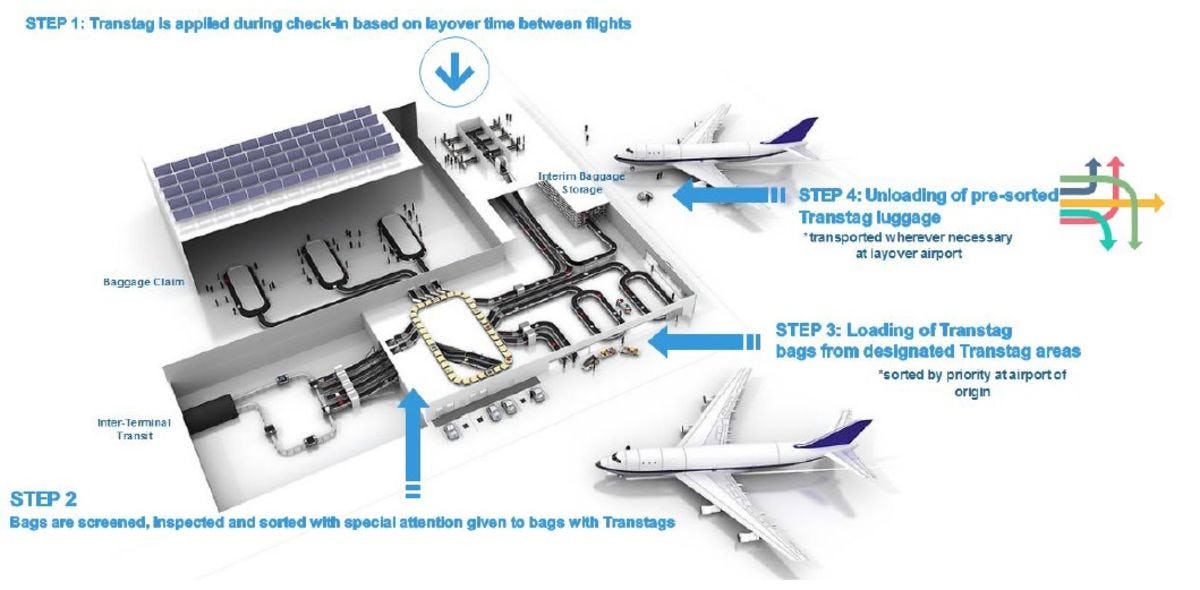

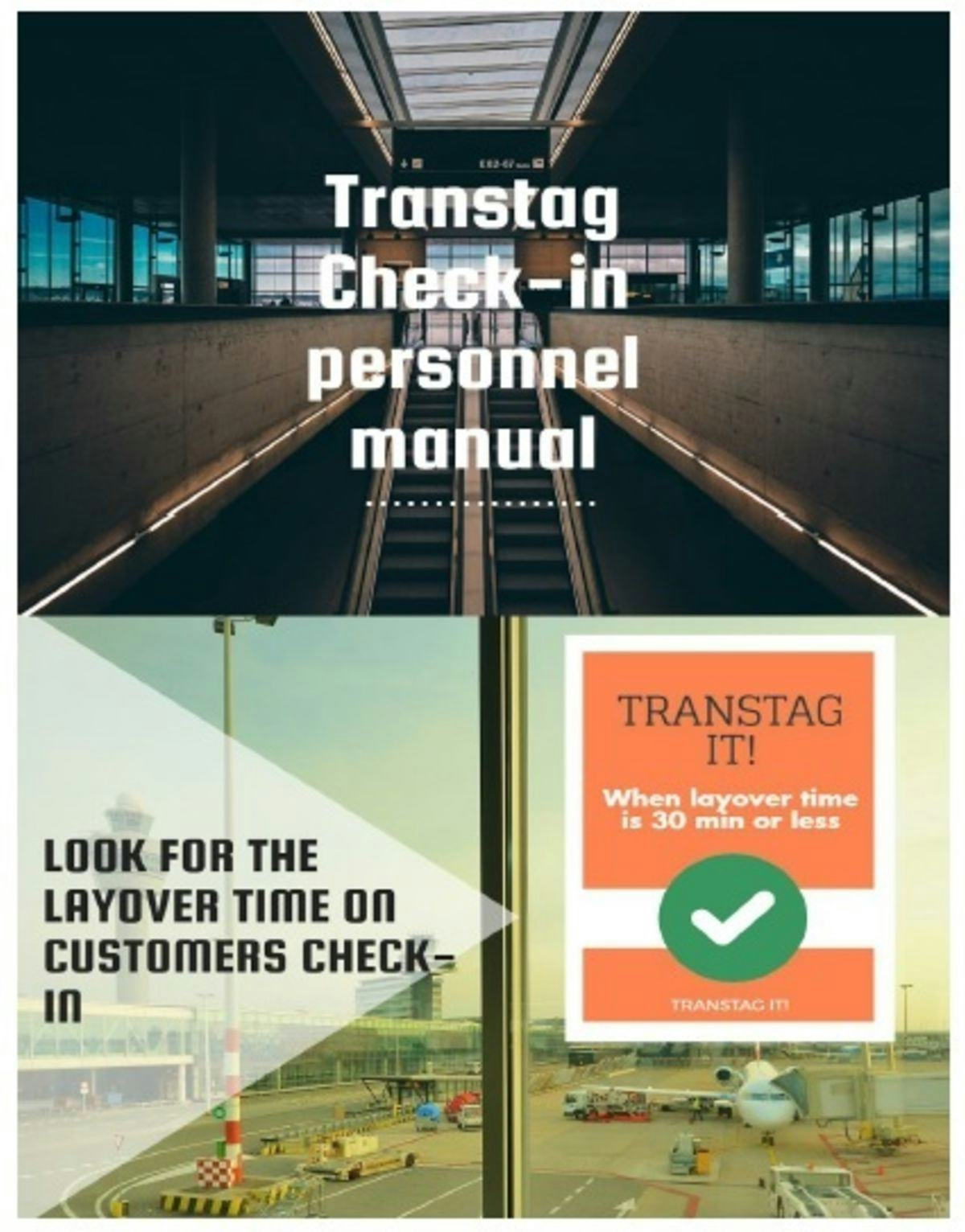

The Transtag system streamlines the process of baggage transfer in between flights and tackles issues involving unnecessary human interaction associated with the baggage system. During the check-in process, airport personnel affix brightly-colored Transtags on luggage with layover time under 30 minutes. Once the bags are processed at check-in, baggage handling system workers identify the bags and get them into the system quicker than terminating bags.

Part of the system involves scanning and removing bags with Transtags from the plane first, and then placing them in designated areas. The bags are then picked up and sent on an express route to their connecting flights, rather than the typical sorting process other bags go through.

Training users in the system is easy; the personnel manual is a single page flyer. What’s more, the system is designed to integrate with current processes without much disruption or additional costs to existing airport systems.

Building a model to measure performance

“In order to show how the Transtag system improves the reliability and efficiency of the current baggage handling system used in airports, we used a discrete event-based simulation software,” says Burke. “We were able to build an effective model that compared systems while being able to monitor which processes improved and by how much time.”

Through their model, the team showed that the Transtag system significantly increases percentage of on-time priority bags and reduces costs for airlines. These improvements in the baggage transfer process can translate into better customer experiences, which can ultimately improve the bottom line for airports and airline companies. As for the students’ experiences, this competition provided them with an opportunity to apply what they have learned in the classroom to solve a real-world systems challenge.

“This was a great group, in our communication and team dynamics, and everyone was an equal member,” says Binyamin. “We ditched the titles and focused on who can do the best job where. The real world lessons lie in project management and team building.”

Mawad asserts that Stevens engineering management coursework was key to providing the team with skills to formulate the solution to the problem. “Going forward, these skills will help me think about every angle of any project that I will work on in the future,” says Mawad, who is looking to stay within the aviation industry as a project engineer.

As for career plans for rest of the team, Burke will be interning at UPS as an industrial engineer over the summer. Binyamin plans to work as a proprietary trader. And Sandford is currently weighing his career options. But in giving advice to future prospective students who are undecided about their career paths, he says, “I find that things usually wind up working out in the end.”

An optimistic message for parents and entrepreneurs who find themselves in flight delays.