Editor’s Note: “Out of the Archives” is dedicated to telling the stories behind lesser-known objects and artifacts from the Samuel C. Williams Library’s Archives & Special Collections.

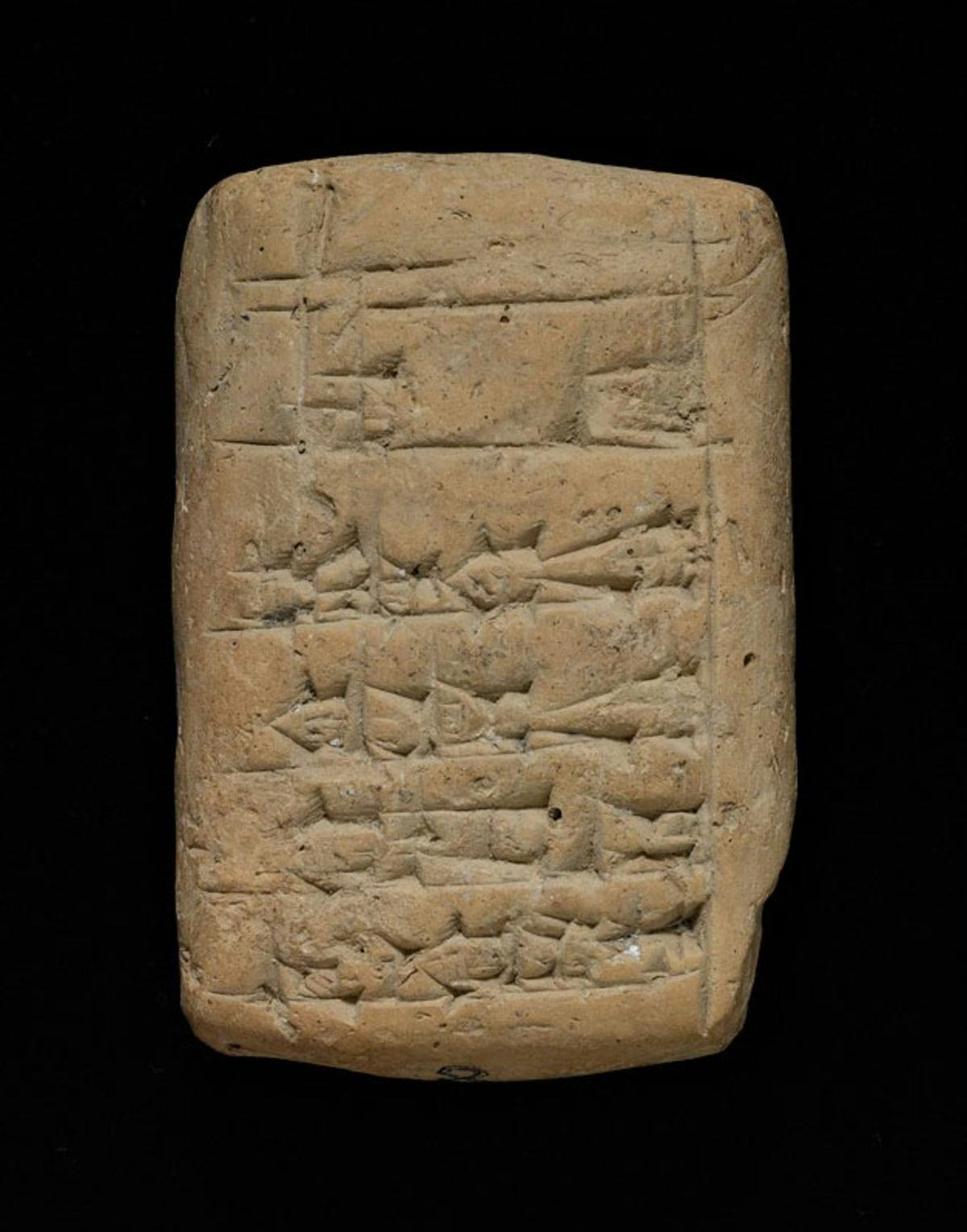

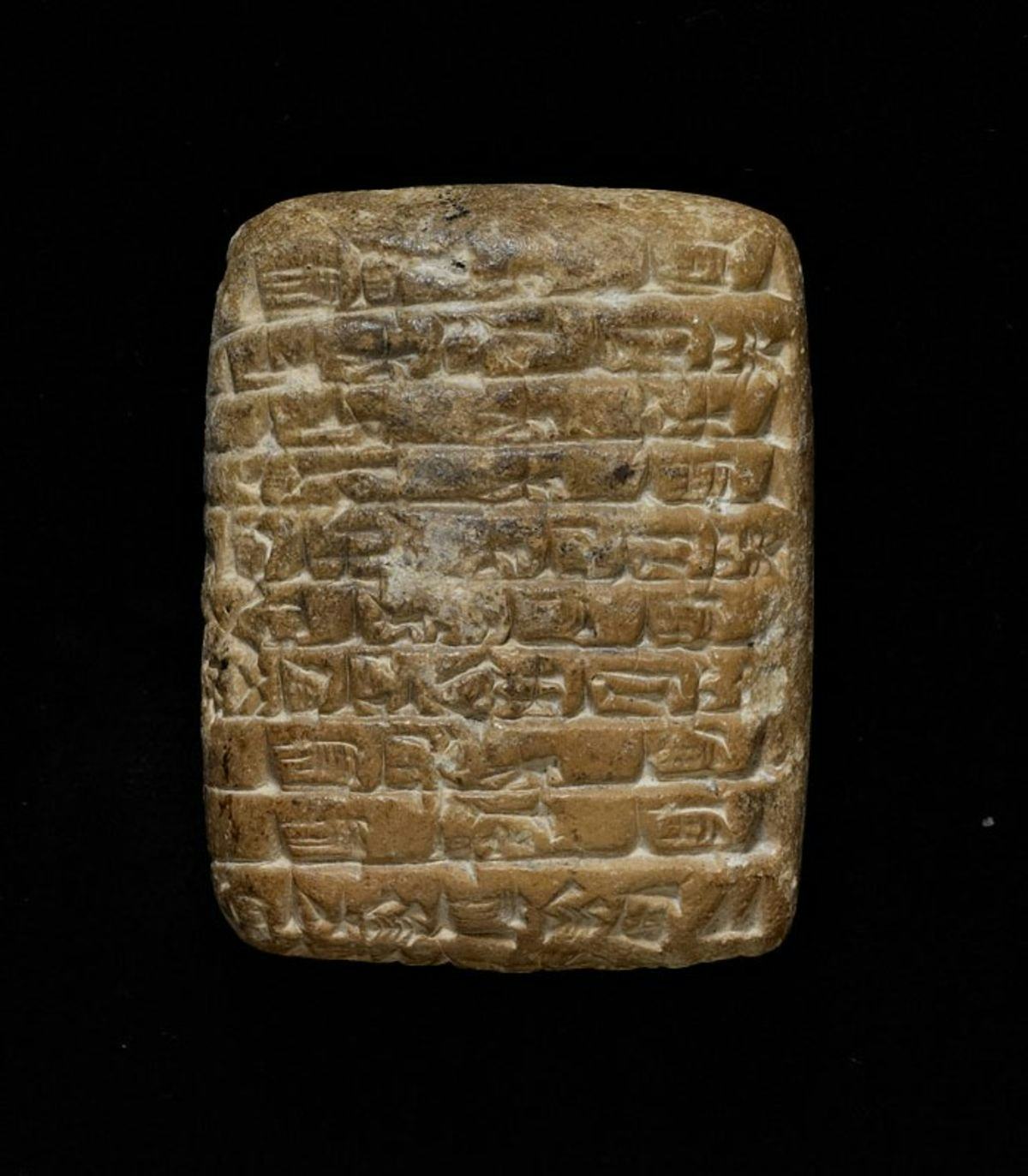

An unassuming storage box on the second floor of the Samuel C. Williams Library houses nine terracotta tablets marked with complex geometric patterns. Though they vary in size, each one is no bigger than the palm of a child. Some look worn, as though they’ve passed through many hands. Others bear their markings in high relief — including the fingerprints of their makers — as if they were created yesterday in a pottery class.

These objects are cuneiform tablets — hard, fired slabs of clay indented with cuneiform, a logo-syllabic script developed by scribes before 3200 B.C. in the Mesopotamian city of Uruk (located in present-day Iraq). Though the script itself is not a language, it was used to write several early languages, including Sumerian and Akkadian, and is widely considered to be one of the oldest forms of writing in the world. So, what were these ancient tablets used for?

“They run the gamut between religious and commercial use,” explains Ted Houghtaling, archivist and digital projects librarian at Stevens’ Samuel C. Williams Library. The library’s Archives and Special Collections has translations of each tablet in its care, as well as information on where they were found. Four of the tablets in the collection detail produce and livestock transactions (including taxes payable in sheep and other animals), two are temple records, two are offerings by pilgrims to Ishtar, the goddess of love, and one is a letter written during the reign of Hammurabi, the influential Babylonian king who issued Hammurabi’s Code, one of the world’s earliest written legal codes.

Stevens’ recent 150th anniversary pales in comparison to the age of the tablets, some of which were created as early as 2400 B.C. So how did these ancient objects find their way to Castle Point? For the answer, we look to the legacy of Dr. Henry Morton, first president of Stevens Institute of Technology — and amateur archaeologist.

“Morton was a Renaissance man,” says Houghtaling. “He had an interest in the physics of light, he wrote poetry and did watercolors. He had an illustrious career which predated his presidency at Stevens. As secretary of the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, he did scientific demonstrations and created illusions using light and experimental heating techniques. He was a showman who knew how to captivate a crowd while also getting across scientific principles.”

Morton was a great educator, teaching physics and chemistry at a variety of colleges and universities. His interest in ancient civilizations was sparked during his own undergraduate days at the University of Pennsylvania. According to a biography published by the National Academy of Sciences in 1915, he and several classmates worked on their own translation of the Rosetta Stone — the ancient text key to interpreting hieroglyphic writing. Though his professional career took him in a different direction, the January 1901 issue of The Stevens Indicator asserted, “President Morton has always kept up his interest in the line of Egyptian and Assyrian archaeology and has accumulated in his library quite a collection of works on these subjects.”