An Affordable, Non-Invasive Hearing Aid Might Be Closer Than We Think

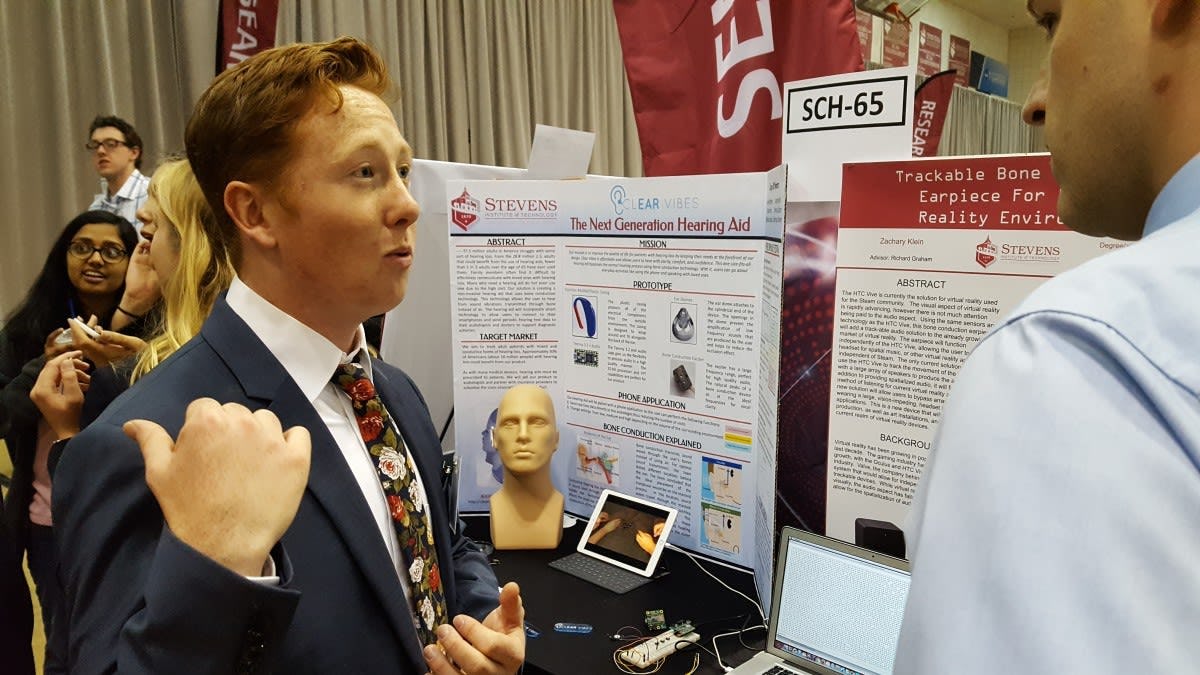

Stevens Senior Design Students Demonstrating a Prototype Bone Conduction Hearing Aid at Annual Innovation Expo

More than 37 million Americans suffer from hearing loss.

Jamie Banhalmi’s dad is one of them.

Jamie’s a mechanical engineering student at Stevens Institute of Technology. Watching her dad struggle with his hearing aid, she realized that most of the devices were ugly, bulky amplifiers. There were other problems, too: outdated technology, uncomfortable design, even social stigma against wearing them. Basically there are far more drawbacks than benefits to hearing aids, as she explained:

So when she had to choose a senior project for Stevens Annual Innovation Expo, she knew exactly what she wanted to do: make a better hearing aid.

And when Allison Brown, Zachary Klein, Dominic LoVasco, Radhika Kasabwala and Dominique Smoyer heard about Banhalmi’s project, they knew they wanted to help. “We thought ‘Let’s make a new one people can get behind’,” Klein said. “Let’s connect it to a phone. Let’s get rid of things people don’t like, like feedback and poor audio quality.” They also knew they wanted to help Banhalmi. “There was a personal aspect to the project,” LoVasco said, citing Jamie’s story. “I saw last year’s expo, and there were a lot of projects sitting in a lab and not making it beyond that. I was drawn to the motivation of helping people, and being able to make a real improvement in their lives.”

United by that goal, the team named themselves Clear Vibes and got to work. They faced challenges almost immediately. For starters, five of them are mechanical engineering students. Klein is an electrical engineering student. “Hearing aids are a subject none of us knew a lot about,” Klein said. “I didn’t know anything about the ear or its anatomy,” Kasabwala added.

The team’s first step? Research. Lots and lots of research.

All that research uncovered a promising solution: bone conduction. Bone conduction is the conversion of sounds into vibrations that are sent through cranial bones directly into the inner ear. This method provides clearer, more nuanced sound than traditional hearing aids and is a popular choice for biomedical manufacturers right now—and a great starting point for the Clear Vibes team. “Our hearing aid design wasn’t originally bone conduction,” Klein said, “but it got rid of the feedback issue.”

That said, bone conduction hearing aids can also be expensive. And uncomfortable. “Current bone conduction hearing aids are invasive,” Kasabwala explained, referring to the fact that most devices on the market require an implant into a person’s skull in order to effectively transmit sound. “We wanted to make one that was less invasive, more cost-effective and comforting.”

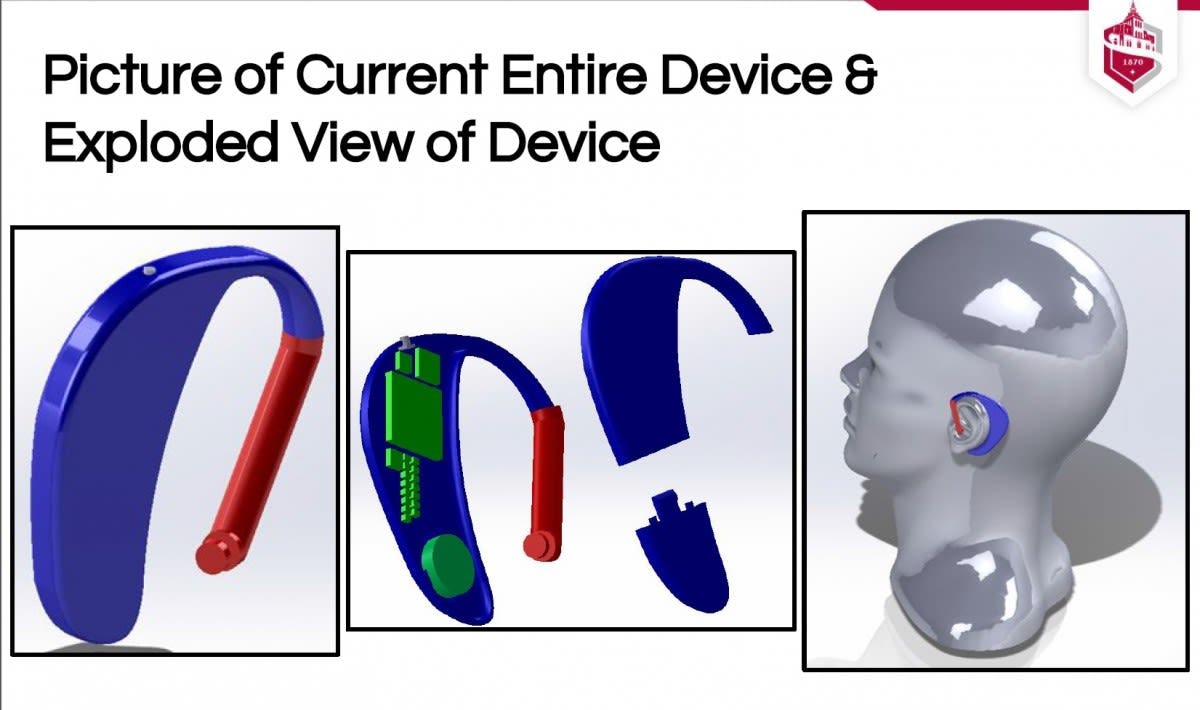

From there, the team began designing their prototype. They knew their device had to have directional audio input and effective frequency filters to ensure clear accurate sound. They also knew they needed to create prototype ear domes to reduce the occlusion effect, which is when the ear canal is blocked and a person hears booming echo-like sounds. Plus, the team needed to do all of that while making sure the device had adequate pressure for bone conduction while fitting comfortably on the ear.

That’s a lot for a senior project.

“Part of the struggle was that this wasn’t one of those projects that people typically came up with for senior design,” Brown said. “We had a misunderstanding of the amount—and type—of work involved.”

“A lot of us are doing things outside the typical electrical engineering or mechanical engineering role,” LoVasco said. Klein agreed, adding: “At the start, you think “This is awesome!” and “We’re gonna have a really cool project!" You see the end, you see the beginning, you don’t see the middle.” Rather than change projects, team Clear Vibes rallied. They switched roles and responsibilities halfway through the semester to better understand—and help—each other.

“It was really hard,” Klein said, describing the transition. “It was hard getting people to do what they’re uncomfortable with,” Brown said. But it paid off. The role switch “revitalized our energy,” Klein said, and gave the team “new points of view,” according to LoVasco. The revitalized team built a working prototype, wrote and implemented testing protocols, and even built an app to help users have greater control over the device.

“We had all these really big goals with time constraints and resource constraints,” Brown said. “We had to pare down our goals a little bit.” That meant they wouldn’t have a fully functional, market-ready hearing aid for the Innovation Expo.

They were not happy about that.

“We’re making headway, but we’re not going to end up with ready-to-go-to market product,” Klein said, “which is what I envisioned in an idealistic sense.”

“It was disappointing to pare our goals down,” Kasabwala said. “We wanted to be at a better place than where we are now.”

That said, the hearing aid does what they want it to. They’ll have a working prototype on display at the Innovation Expo. They’ll also have a visual mockup of the final design and a demo version of the app.

In the future, the team hopes that someone else will continue their idea. “That way we can see the next stage of it,” LoVasco said.

Stevens hopes so, too.

Learn more about Jamie and Team Clear Vibes story here: