Green roof expert Ed Snodgrass speaks to Stevens about the future of urban ecology

Ed Snodgrass is the owner and president of Emory Knoll Farms, Inc. and Green Roof Plants in Maryland. He’s also a world-renowned expert on green roofs—and friend of Elizabeth Fassman-Beck.

Early in the morning of August 17, Snodgrass helped associate professor Fassman-Beck and her students wash and plant plants on the Stevens Institute of Technology's Living Laboratory green roof. The green roof setups are urban bioretention solutions designed to study and prevent rooftop runoff. In order to do that, Fassman-Beck and her team are testing different recipes for lightweight growing media.

Plants are a key part of those green roof setups. That’s where Snodgrass comes in.

“These are industry standard plants,” Snodgrass explained. “Since [Fassman-Beck and her students] are looking at just the nutrient outfall, we didn’t want to get too fancy with plants. This would represent the typical assembly in the New York City/New Jersey area…. If you get into stretching the envelope in terms of plants, it may skew the other data.”

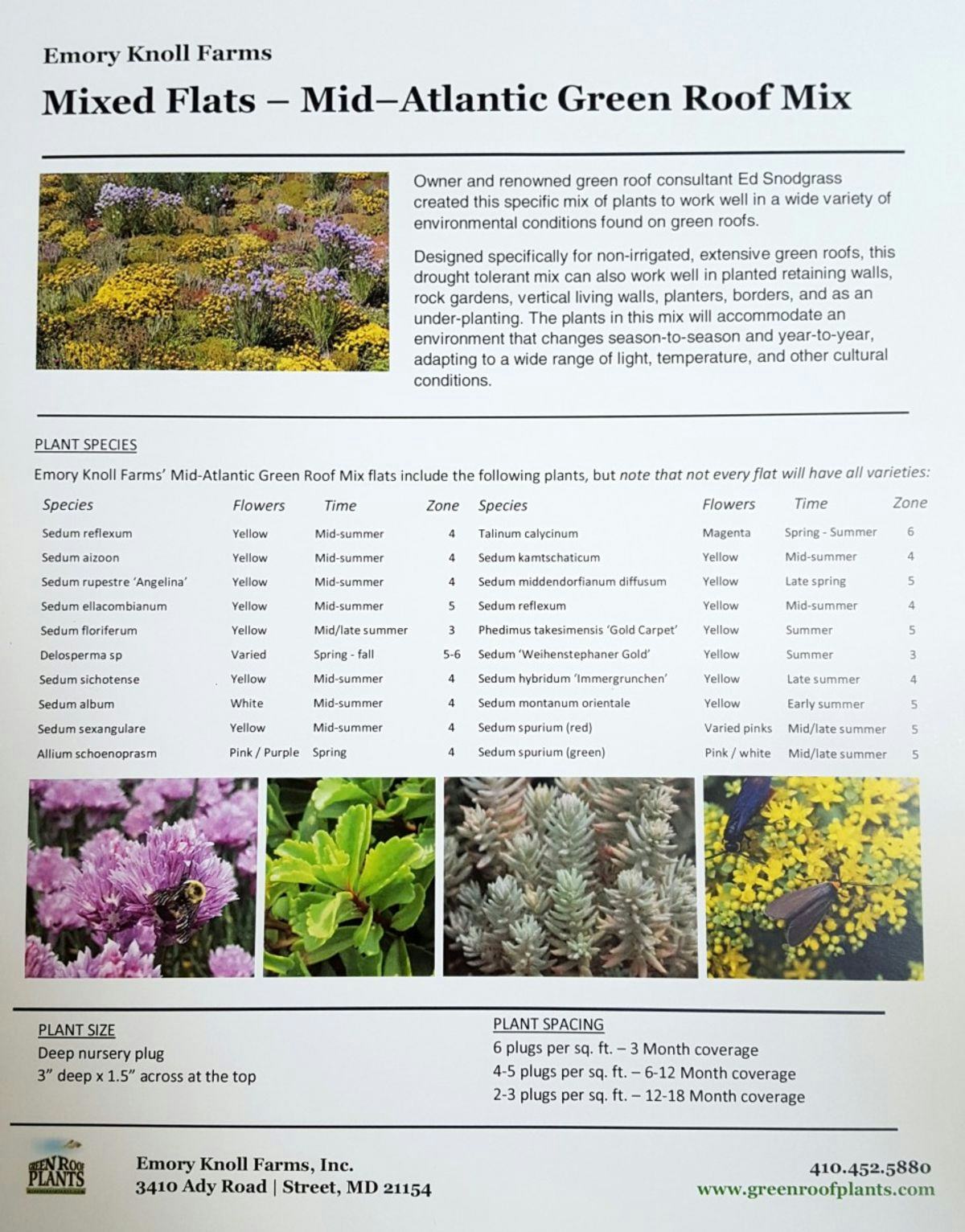

An example of the kinds of plants used in the Living Laboratory green roofs. CREDIT: Emory Knoll Farms.

Emory Knoll Farms was kind enough to donate those plants to the Living Laboratory. They may be industry standard, but they’re above average in terms of quality. “These are all produced without chemicals or insecticides or pesticides. We designed our own propagation media. It’s all post-consumer,” he explained. “We really think that the ethos we’re seeing on the roof should extend down the supply chain. We should have a very low footprint as a manufacturer. That’s part of the overall solution.”

Again, the overall solution for the Living Laboratory green roof is figuring out the right mix of materials in each planter to control the volume of water. But the key to making that happen is in how the system works together.

“No one part of a green roof really pays for itself,” he explains. “It’s the aggregation of benefits that gives you return on investment—and that’s really different than typical civil engineering infrastructure.”

Snodgrass also spoke to Stevens about why New York City can’t turn all its rooftops into gardens, how storm runoff has become more complicated, and what he’s most interested in seeing from this experiment. Listen here:

Sorry about the background airplane noise!

For all of those difficulties, Snodgrass is still excited by the Living Laboratory. “A farmer like me gets to work with a civil engineer like Elizabeth. It brings together a group of people in a collaborative way you wouldn’t see in previous incarnations of city design, where everyone does their piece and then they don’t have to talk to anyone else,” he said.

Snodgrass has helped do this for universities all over the world from universities in Maryland, North Carolina and Pennsylvania to universities in Australia, New Zealand and China. And he doesn’t plan on slowing down.

“These are the jobs of the future,” he said. “In the 1920s, colleges weren’t teaching students how to build carriages and buggies; they were teaching [them] how to build aeroplanes. You don’t teach the technology of the day, you teach the technology of the future.”

Teaching the technology of the future is what Stevens is all about.