A letter from Frances Perkins, first female U.S. Secretary of Labor, reveals her friendship with a Stevens family member

Editor’s Note: “Out of the Archives” is a new department within The Stevens Indicator dedicated to telling the stories behind lesser-known objects and artifacts from the Samuel C. William Library’s Archives & Special Collections. Explore more at library.stevens.edu/archives.

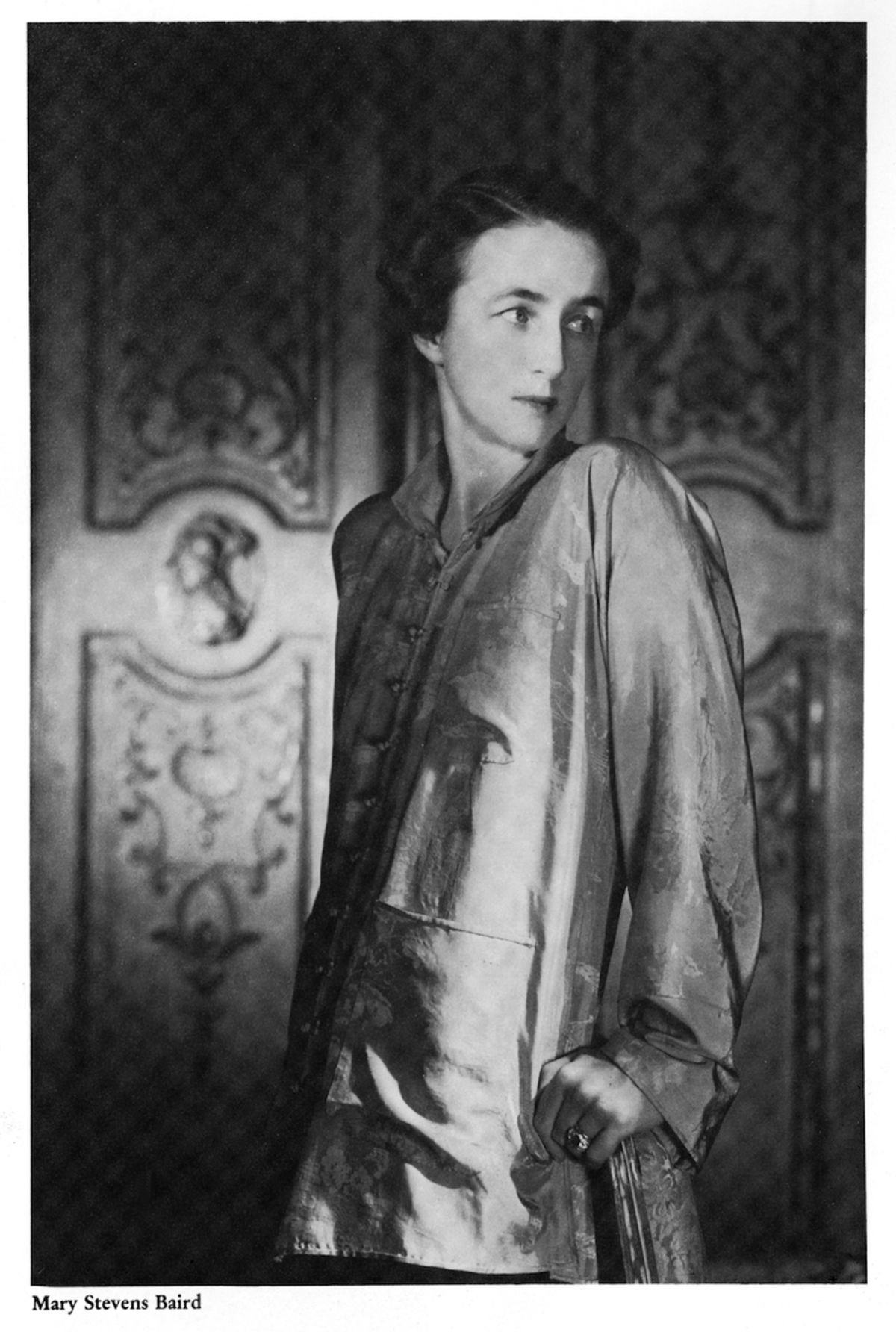

During a recent review of unprocessed materials in the archives, Leah Loscutoff, head of Archives and Special Collections at Stevens’ Samuel C. Williams Library, learned of a yellow envelope postmarked January 21, 1941. The envelope bears an intriguing return address printed in simple block letters: “The Secretary of Labor, Washington.” Inside, three pages of embossed letterhead provide a window into the ongoing correspondence of two notable women — Mary Stuart Stevens Baird and Frances Perkins. Here, Loscutoff shares the find , explaining the significance of these individuals and what they were discussing.

Two influential pen pals

Stevens Baird, the recipient of the letter, was the granddaughter of Edwin A. Stevens and Martha Bayard Stevens, the founders of Stevens Institute of Technology. Born at the family estate (affectionately known as Castle Stevens) in 1901, she lived on Castle Point until around 1910, when the structure was sold to the university for use as administrative office and dormitory space. Stevens Baird maintained close ties to the university throughout her life, serving as an honorary member of the Board of Trustees and hosting an annual treasure hunt and picnic at her Bernardsville, New Jersey, estate. She also donated the vast Stevens Family Collection to the Samuel C. Williams Library, now on permanent display in a room bearing her name.

Prior to the United States’ involvement in World War II, Stevens Baird worked with Young America, a branch of the English war relief effort, serving refugees in the United Kingdom. Later, she served as an investigator for the U.S. Army, Second Service Command. Like other members of the Stevens family, she was deeply committed to the cause of prison reform, serving on a variety of correctional executive boards in New York and New Jersey over 30 years. In the late 1940s, she represented the United States at the International Penal and Penitentiary Congress at The Hague.

Perkins, the letter’s author, had an exceptional record of public service. Holding a master’s degree in economics and sociology from Columbia University, she became head of the New York office of the National Consumers League in 1910. The following year, Perkins witnessed the devastating Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, in which 146 workers died because of the building’s lack of fire escapes and other safety measures. The tragedy inspired her to lobby for worker’s rights — especially the interests of women and children — through various positions within the New York state government.

After getting to know her during his time as governor of New York, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt nominated Perkins to join his cabinet as Secretary of Labor in 1933. The first woman to serve in a U.S. presidential cabinet, she worked on some of the New Deal’s most influential initiatives, including the Social Security Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which established a minimum wage, maximum weekly working hours and a ban on child labor in select industries.

A peek into their correspondence

Though Loscutoff says it is unclear how these women met or when they began their correspondence, the familiarity and depth of the letter suggest that they built a strong friendship. The letter discusses Stevens Baird’s recent quarantine after measles exposure, references to FDR’s famous “The Four Freedoms speech” and a suggestion to Stevens Baird by Perkins that she should get in contact with the Women’s Division of the National Democratic Committee.

Without the context of earlier letters, some passages remain vague, such as the following assertion by Perkins: “I am coming more and more to the feeling that we are in a phase of world development when it is ideas that count more than actions. I have always been an activist and tended to scorn the people who sat in ivory towers and thought. Now I think we may perish here in America for lack of the ability to formulate and adhere to ideas.”

Because the letter was written in early 1941, Loscutoff believes Perkins could have been reacting to the spread of Nazi rhetoric throughout Europe and what that might mean for a neutral United States. “I think American people at the time were more isolationist. They didn’t want to get involved in a war that was overseas,” says Loscutoff. “But I think they were realizing that we couldn’t just sit by and let this happen.” By the end of the year, the idea of war became reality following the attack by Japanese forces on Pearl Harbor.

The letter holds a unique place in the Stevens archives, serving as an example of intellectual dialogue between two women about the state of the world during a time when women weren’t expected to be vocal about politics. By sharing ideas and taking action for change, both women moved important social and political causes forward, helping to pave the way for the next generation of women in public service.