Out of the Archives

In celebration of 150 years of Stevens Athletics in 2022, The Indicator visited the Samuel C. Williams Library’s Archives & Special Collections to learn more about the sport that started it all — football.

For many colleges and universities across the United States, football borders on a religious experience —bringing the faithful together every Saturday to tailgate, cheer on the home team, revel in victory or commiserate in defeat. Though college football and the culture that surrounds it feels like a time-honored tradition, the version of the sport we watch today is relatively new.

The first-ever game of college football was played in New Brunswick, New Jersey, in 1869 between Rutgers University and Princeton University (then known as the College of New Jersey). In the years that followed, several other colleges fielded teams, including Yale University, Columbia University, New York University — and Stevens Institute of Technology, which played its first game against Columbia in 1872, just two years after the university’s founding. From that first game through its last in 1925, Stevens’ football team played for 52 seasons. These early student-athletes not only launched the university’s fledgling athletic program but were also part of a larger movement to define and standardize intercollegiate football.

A Lawless Game

Sports historian Jim Weathersby has called these early years of the sport “the Wild West of college football,” during which there were no standardized rules for gameplay. Instead, visiting teams would play by the home team’s rules. Games were scheduled informally between personal contacts on the respective teams and were often canceled if not enough players showed up (in those days, around 20 players from each team were on the field at one time).

“You wouldn’t recognize the way it was played then versus how we conceive of football now,” says Ted Houghtaling, archivist and digital projects librarian at the S.C. Williams Library's Archives & Special Collections. “It was essentially rugby and soccer smashed together into one sport.”

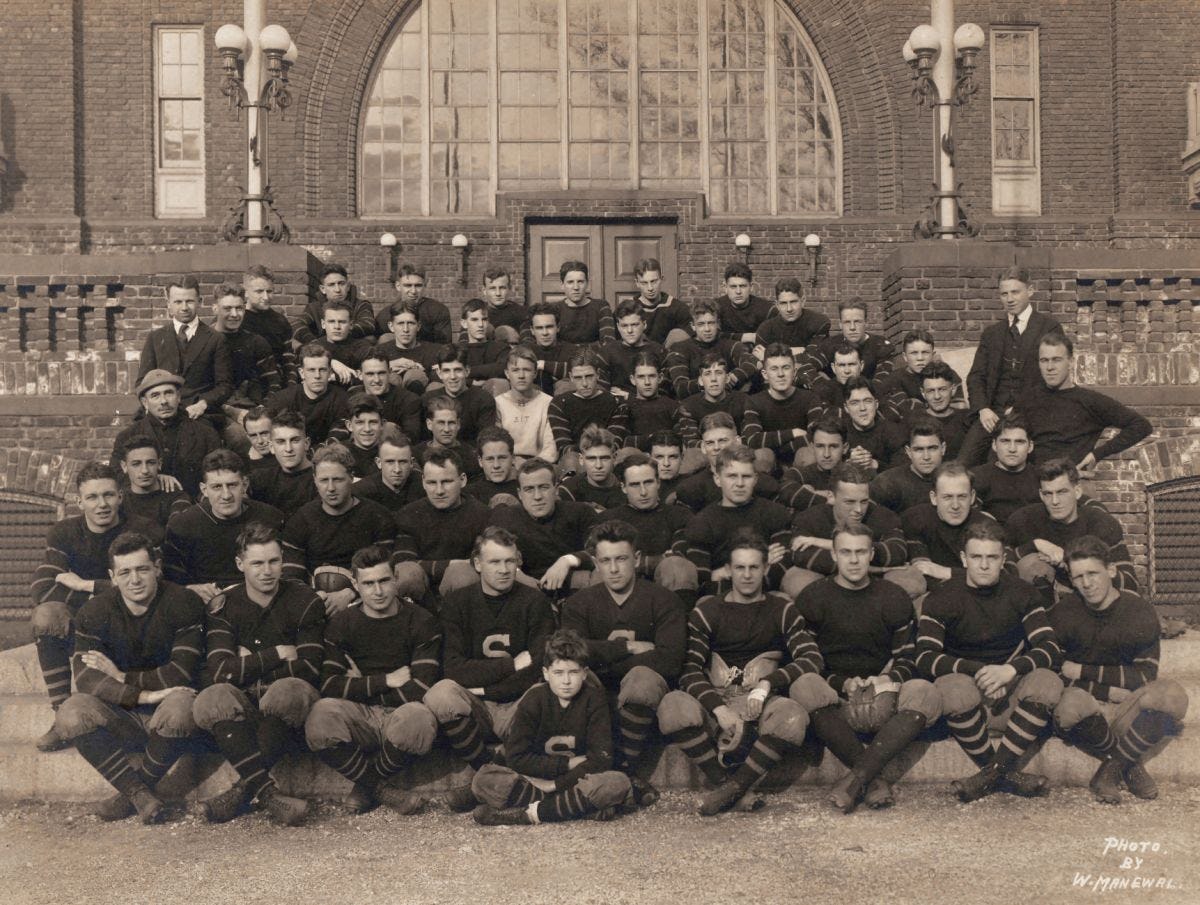

Like rugby, football of the late 19th century was a rough game. Players wore little to no protective equipment and made frequent trips to the infirmary to patch up inevitable cuts and bruises. As the game increased in popularity, however, there was an uptick in more serious injuries and fatalities.

The game’s violence attracted national attention, making clear a need for standardized rules. Stevens met with Princeton, Yale, Rutgers and Columbia at The Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City in 1873 to find consensus on scoring, passing and tackling, and established the Intercollegiate Football Association to try to enforce the new rules.

A subsequent meeting in 1876 (which Stevens did not attend) further refined the rules, reducing the number of players on the field to 11 and replacing kicked goals with touchdowns as the primary means of scoring.

The Undefeated Season of 1911

“College sports were huge in developing a sense of collegiate identity, and rivalry, pride and culture at Stevens,” says Houghtaling.

Much of the earliest documentation of Stevens football is based on oral histories, but when The Stevens Life (1890-1899), The Link (1890) and The Stute (1904) began publishing, they featured extensive coverage of the sport, including play-by-play reporting and cartoons celebrating victories and lampooning opponents.

Stevens’ then-president, Alexander Humphreys, extolled the virtues of football and athletics in general, calling physical education integral to the development of a well-rounded man.

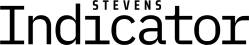

Enthusiasm was at an all-time high in 1919 when the varsity team completed the season with a 7-0 undefeated record. This included a 13-0 victory against that year’s “strongest opponent,” Columbia University, witnessed by 2,500 Stevens fans. The team’s captain, Leonard C.M. Bloss, Sr. (Class of 1920) and Ralph “Swede” Carlson (Class of 1921) were among the team’s standout players — both were inducted posthumously into the Stevens Athletic Hall of Fame.

A December 1919 Stute article recounted the atmosphere of celebration following the team’s undefeated season: “Almost 1,000 undergraduates and alumni gathered in the gym … at a dinner and smoker in honor of our undefeated 11. Every man was given a corn-cob pipe [emblazoned with the season’s score] and a bag of Prince Albert [tobacco] at the door.”

Football’s Demise — And Athletics’ Rise — At Stevens

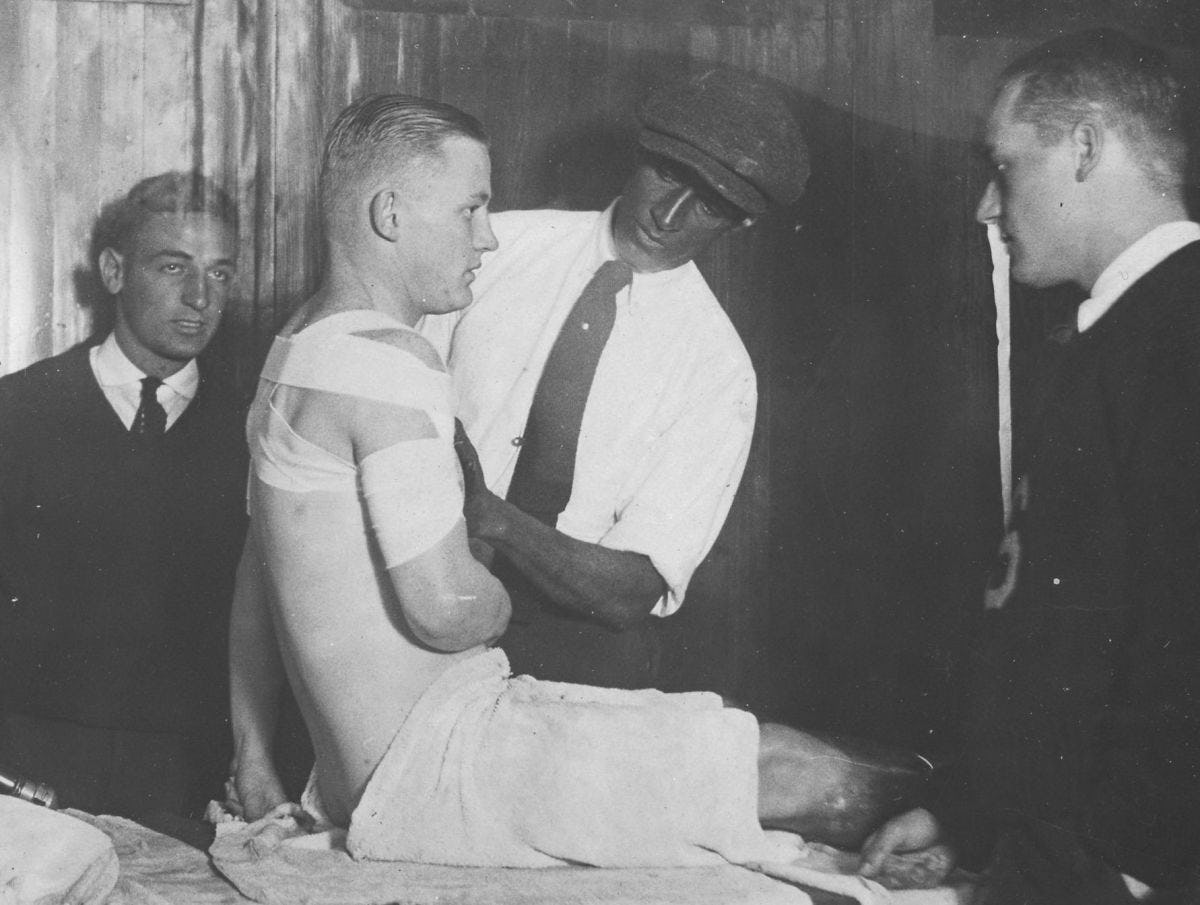

In the years that followed Stevens’ exhilarating 1919 season, the program’s record began to decline. “Since 1921, the football seasons have been periods of nightmares,” wrote J.A. Davis, Stevens’ then-director of physical education, in a November 1924 issue of The Stevens Indicator.

“It became too competitive,” explains Houghtaling. “This is when you start to see the professionalization of college athletics.” Stevens always based its admissions criteria on academics, while some of its competitors started to offer athletic scholarships as well as funding for better training and facilities. As Stevens continued to lose to better-resourced teams, serious student injuries increased. When these injuries began to interfere with students’ ability to complete their coursework, President Humphreys made the unpopular decision to dissolve the program in June 1925.

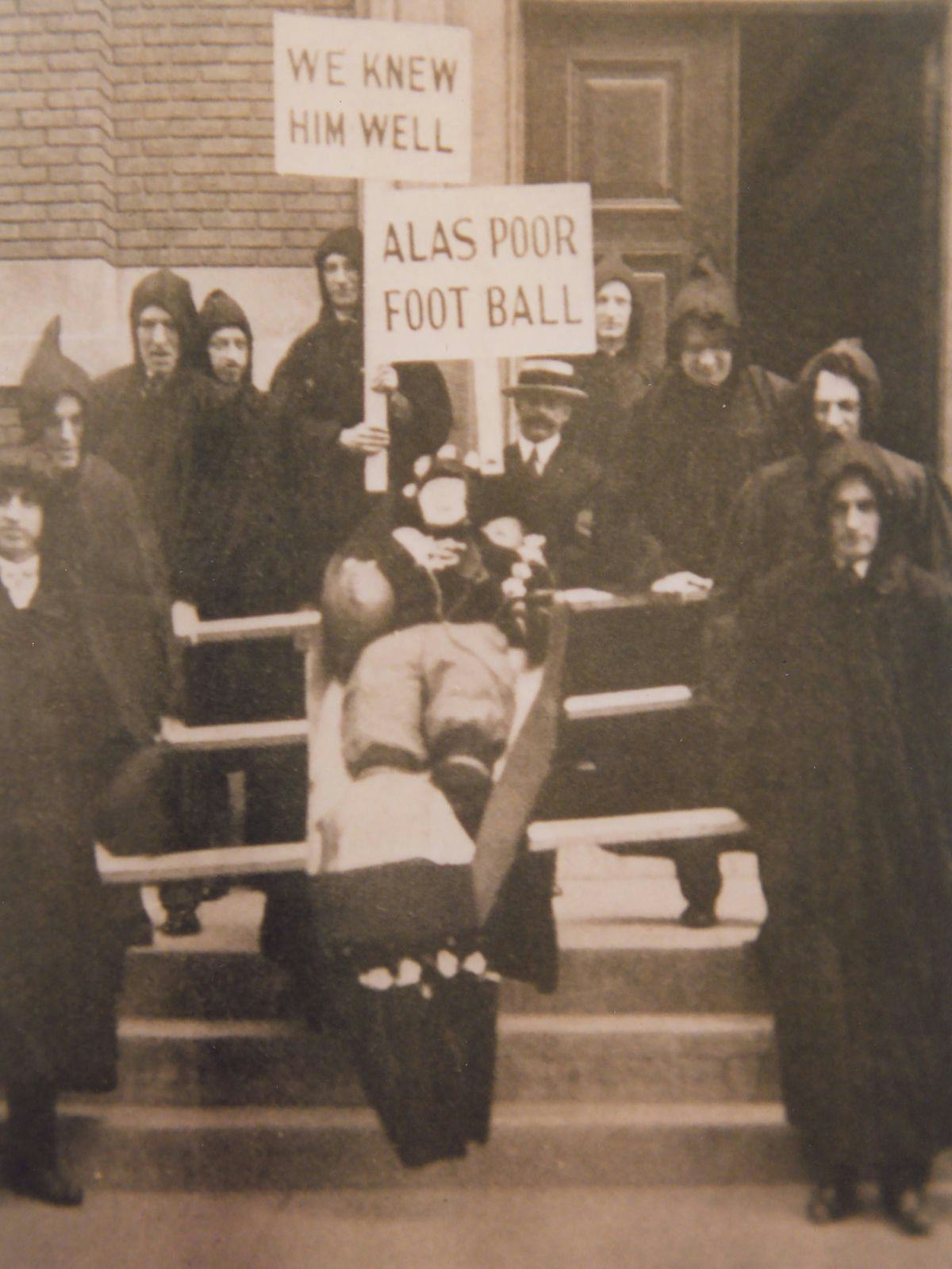

In response to the ban, there was an outcry from students and alumni, who wrote letters to the president and numerous editorials in The Stute. On Alumni Day in 1926 (the first following the ban), a mock funeral was held for football, in which former players served as pallbearers, carrying an effigy of the beloved sport in a casket onto the athletic field.

Despite these protests, Humphreys’ decision remained firm and there has not been an intercollegiate varsity football team at Stevens since (intramural and interclass competitions, however, did continue). Though football is no more, this first sport paved the way for programs that have thrived for more than a century, notably lacrosse, baseball and basketball.

Athletics remains a key part of the Stevens experience, fostering teamwork, discipline and camaraderie among today’s Ducks. Learn about Stevens’ history-making 2021-2022 athletics season.

— Erin Lewis

“Out of the Archives” is dedicated to telling stories behind lesser-known objects and artifacts from the Samuel C. Williams Library’s Archives & Special Collections. Explore more Stevens history.