Building a More Equitable World Through Affordable Housing Systems

Ground-breaking engineer, city planner, activist, James Braxton'37 Hon. D.Eng.'87 left a legacy of extraordinary achievements

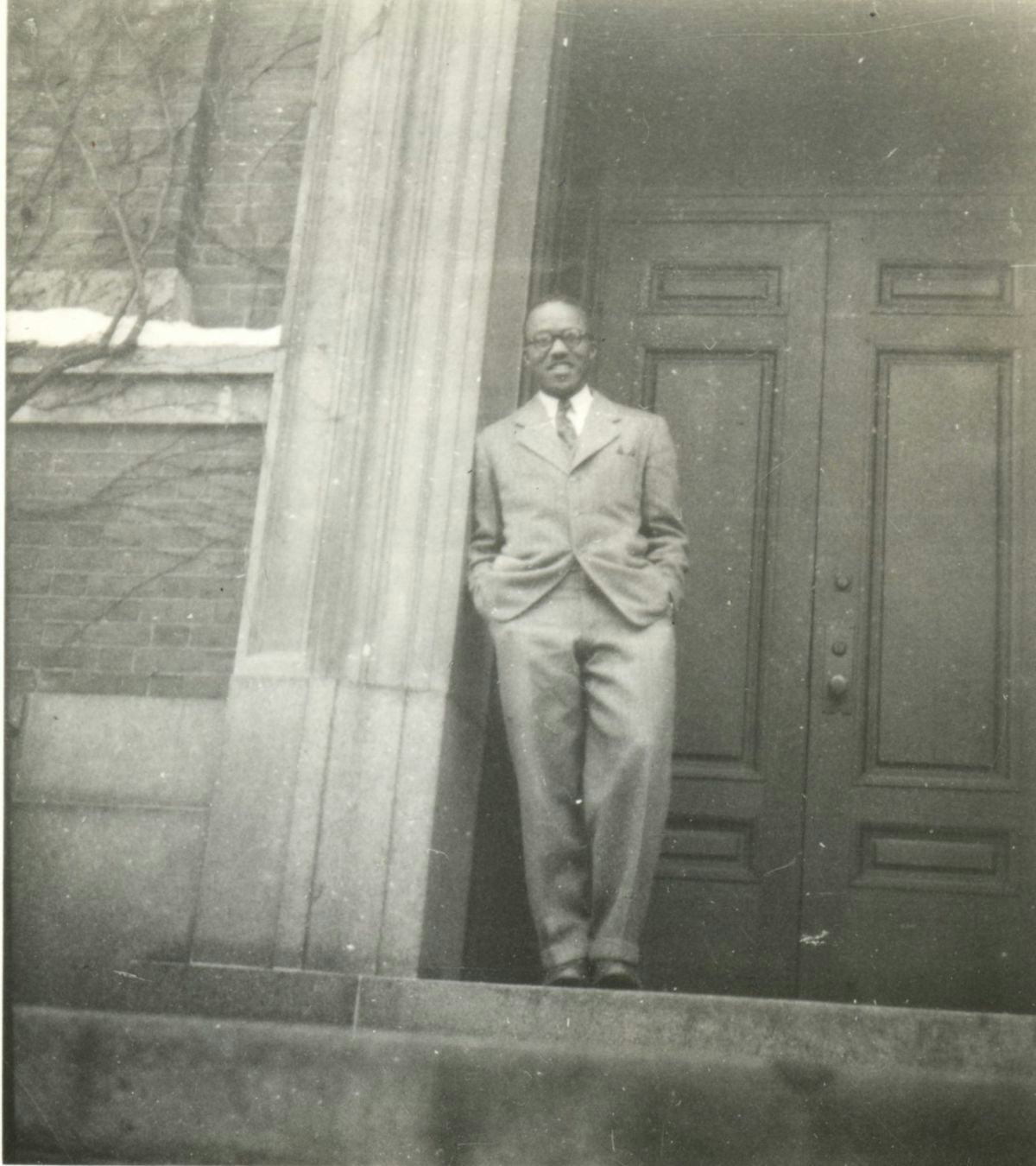

Editor’s Note: In 2020, Virginia Braxton, the wife of the late James Braxton ’37 Hon. D.Eng. ’87, generously donated her husband’s papers to the Samuel C. Williams Library. Here, Leah Loscutoff, head of the library’s Archives and Special Collections, traces this alumnus’ extraordinary life and legacy through family interviews and this new collection of his letters and photographs.

When Dr. James “Jim” Sylvester Braxton ’37 Hon. D. Eng. ’87 was a young man, he wrote out a list defining success. Inspired by the writer Ralph Waldo Emerson, Braxton noted: “to leave the world a bit better.” Poring through The James Braxton Papers that were recently donated by his widow, Mrs. Virginia Braxton, reveals Braxton’s commitment to that early inspiration and has provided deep insight into the unexplored life and career of this extraordinary Stevens alumnus.

Braxton was the second Black student to graduate from Stevens, after Randolph Montrose Smith Class of 1924. Born in Waukesha, Wisconsin, the son of a minister and a homemaker who moved East, he graduated from Lincoln High School in Jersey City, New Jersey, at the top of his class. He secured a four-year Edgar B. Bacon scholarship before entering Stevens in the fall of 1933. Braxton was one of the most active members of his class, a member of the engineering honor society Tau Beta Pi, and in 1937 pledged and was admitted to the Jersey City Chapter of the prestigious fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha, the first fraternity chartered for Black men in America. (A chapter was established at Stevens 82 years later, in 2019.)

In The Link yearbook biography, Braxton is described as having “an enviable scholastic record,” appearing consistently on the dean’s list. “We expect big doings from this young engineer, and we are sure Jim won’t disappoint us.” Not only did he not disappoint, he excelled spectacularly.

A thriving career, prominent friendships

After Braxton graduated from Stevens in 1937, America was still greatly affected by the Great Depression and Black Americans had limited job opportunities.

Nonetheless, he landed a position with Lockwood-Greene Engineers to help build a power plant at Atlanta University, a historically Black institution that is now known as Clark Atlanta University. Braxton enjoyed an active social life while in Atlanta, which was becoming a mecca for Black scholars and artists. Years later, Braxton reminisced about his friendship with the artist Romare Bearden and dinners with the prominent scholar, activist and author W. E. B. Du Bois, who taught at Atlanta University from 1934 to 1944.

Lindsey Swindall, a teaching assistant professor at Stevens’ College of Arts and Letters, points to the significance of this period in Du Bois’ long career, “Though the aging Du Bois was approaching his seventh decade, he was still doing groundbreaking historical research that challenged the conventional white supremacist perspective of American history with books like Black Reconstruction in America.”

In 1941, Braxton finished his work in Atlanta and moved on to other projects with two significant Black architects: Samuel Plato and Hilyard Robinson. Plato and Robinson were both early trailblazers, and Braxton worked as their chief engineer and engineering consultant, respectively. Plato was the first Black architect to receive federal building contracts, and became best known for his work on federal U.S. post offices nationwide. Robinson is still highly regarded for his housing designs.

Braxton worked with Plato on the homefront during World War II as a skilled engineer, and together they built the Langston Stadium Residence Halls, which were temporary buildings designed to provide housing, recreation, food and medical facilities for 900 women in the wartime labor force in Washington, D.C.

From Liberia to Harvard to London

Braxton briefly took a position as an instructor at Howard University from 1943 to 1944, but went on a leave of absence in 1944 to help Robinson on a project to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Republic of Liberia in Africa. A hitch in the project sent Braxton home earlier than expected and this allowed him to pursue his next goal sooner: completing the city and regional planning master’s program at Harvard University.

Soon after Braxton entered Harvard, he was awarded a Julius Rosenwald fellowship. Civil rights activist Julian Bond referred to the list of Julius Rosenwald fellowship grantees as the “who’s who of Black America in the 1930s and 1940s,” and Braxton shared this renowned honor with literary luminaries and scholars Langston Hughes, W. E. B. Du Bois and Maya Angelou. He then spent the summer of 1946 studying with the Ministry of Town and Country Planning in England, where he saw firsthand the destruction London endured during World War II.

Chicago-bound, and marching with Dr. King

In 1950, Braxton received a letter from city planner Martin Meyerson, chief of planning for the Chicago Housing Authority, requesting that Braxton join his team. Meyerson wrote, “We are still looking for competent, top-level planners and I still can’t think of anyone who would be of greater utility to the housing authority than yourself.” Braxton accepted Meyerson’s offer, and in 1950 he moved to Chicago to join the Housing Authority, making the city his home until 2015 when he passed away at the age of 101. In 1965, Braxton was promoted to assistant chief engineer of the metropolitan sanitary district of Chicago. He was the first Black engineer to hold a top position in that district.

Braxton’s career in Chicago helped shape the remainder of his professional and personal goals, which included working on affordable and equitable housing — a central theme throughout his career and a key issue in the civil rights movement. Throughout Braxton’s papers there is documentation of his meaningful responses to racial inequality, including his personal experiences with discrimination. In 1951, Braxton wrote to the head of an insurance company that had just denied him a basic health policy because of his race. He cogently pointed out, “Health experience and longevity are not racial traits ... but rather are the result of unhealthful living conditions produced by discrimination in housing and lack of economic equality.”

In 1966, Martin Luther King Jr. moved to Chicago to address the poor living conditions of Black populations in American cities. Already active in the civil rights movement, Braxton joined Dr. King’s march on August 5, 1966, protesting housing discrimination in Chicago. During this march, a group of hecklers nearby turned violent, injuring Dr. King by throwing a large stone at his head. When Mrs. Braxton was recently asked how her husband would have responded to the current Black Lives Matter movement, she said, “Like every Black person in America, he knew there is always a potential for violence at the hands of the police. He would have supported the peaceful protest of the Black Lives Matter movement, as well as efforts to improve Black lives through legislation, court cases and administrative actions.”

Toward the end of his career, Braxton received two great honors from Stevens: an alumni achievement award in 1970 recognizing his work in the government sector, and an honorary doctorate in 1987. In Braxton’s 1987 speech he said, “Last year I obtained a U.S. Patent on a systems approach to housing construction. Although the system will permit construction of any type of building, anywhere, the shortage of affordable housing, and the presence of so many unemployed in the inner city make it an attractive starting place.” This cutting-edge system included pre-manufactured interlocked masonry blocks that implemented the best professional engineering standards. These could be easily assembled by unskilled labor forces, which addressed both the affordable housing shortage and unemployment in inner cities, which were often the biggest barriers to more equitable living conditions. “The system could also help address the effects of climate change by quickly building homes destroyed in our increasing natural disasters,” says Mrs. Braxton. Challenges in raising funds for research and development prevented universal adoption of The Braxton System, and, as Mrs. Braxton reflects, “Jim was always ahead of his time.”

Fortunately, Braxton’s visionary ideas that affirm his early inspiration of success “to leave the world a bit better” are now preserved in the Stevens archives for future generations to discover and build upon his lifetime of success.

To view a recent webinar on the life of James Braxton that features his wife and others as panelists, visit Stevens.edu/BraxtonRoundtable

The James Braxton Papers are now available to researchers by appointment at the Samuel C. Williams Library. For information, email Leah Loscutoff at Leah.Loscutoff@ stevens.edu